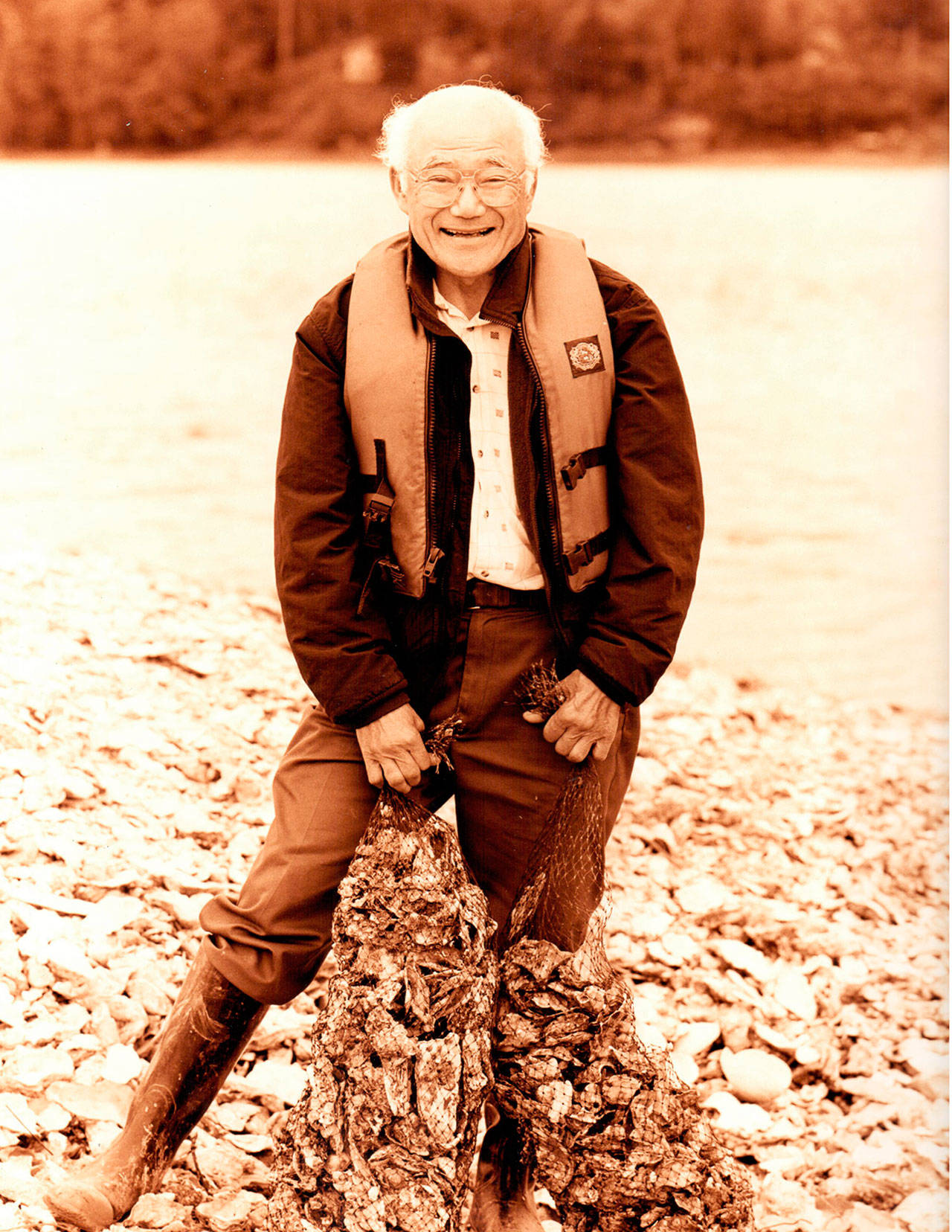

What was supposed to be a short historical tribute to retired oysterman Jerry Yamashita, 95, of Seattle, took on a different meaning once Leaping Frog Films got into the project.

“Ebb & Flow — A Japanese family, an oyster and how they influenced Pacific Northwest history,” a 77-minute film,“is the evolution of a much bigger story. It’s a life story, a family story, and a historical look at something that could have been lost,” said Shelly Solomon, co-founder of Leaping Frogs Films with Kent Cornwell.

Solomon, a restoration biologist and water quality specialist, and Cornwall, a designer, have been making documentary films with an environmental slant for a decade through their Nordland-based production company. Among them have been “River As Spirit — Return of the Elwha” and “Restoration of the Olympia Oyster.”

“These are types of stories that if we didn’t do the film they would be lost. No one was familiar with a lot of Jerry’s family history,” Cornwall said.

“This is not a one-subject kind of thing that most documentaries end up being.”

The film tells the story of the Yamashita family, its struggles and triumphs, and its role in the West Coast shellfish industry. It will be screened at 5 p.m. Saturday in the Little Theater on the Peninsula College campus at 1502 E. Lauridsen Blvd., Port Angeles.

General admission tickets are $20 and include wine from Port Townsend Vineyards and fresh oysters from the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, whose members will discuss their experience growing the Pacific oysters featured in the film.

Students and alumni with identification will pay $8. Those younger than 21 will not receive wine.

Audience members younger than 21 who are not students will pay $13 — and also receive no wine.

The film, completed a little more than a year ago, contained revelations for everyone involved, Solomon said.

“We didn’t want to make it into a standard documentary,” she said.

“It’s more an eavesdropping into a conversation between a father and a son. It’s a day in a life of a man who wanted to find out about his family history. He learned much more than he hoped he would.”

Said Cornwall: “Some viewers have said they wish they had sat down with their dads and talked with them before they passed away.

“The film does different things for different people.”

The story is told in first person by 93-year-old Jerry (Elichi) Yamashita and his son, Patrick, and details the history of the shellfish industry and the struggle of Jerry’s father, Masahide Yamashita, who came to the United States in 1902 at the age of 19. The film uses archival footage to help put the story into context.

By wondering “what if,” and using his connections to his home country, Masahide Yamashita played a pivotal role in establishing the Pacific oyster in Washington in the 1930s.

“During the Gold Rush Days in San Francisco, every time they would discover gold, they would celebrate by slurping those little Olympia oysters, those little native delicacies,” Solomon said.

“The irony is that mining gold causes water pollution. It gradually led to the species’ demise in the area.”

Solomon said harvesting continued farther and farther north and the native oyster continued its decline due to demand and overharvesting. The industry was scrambling to save itself. They brought in the eastern oyster that did not do well. Everything failed. They were in almost complete collapse.

Solomon said Japanese vendors at the Pike Place Market wondered if the oysters they ate as children would grow here.

Masahide Yamashita saw a solution.

He figured out how to bring another species to the Northwest to create the largest shellfish industry in the United States.

He focused on using baby oysters called “seeds” that survived the long journey on the shell of the adults. They were planted in Pacific Northwest waters, grew quickly, and thrived.

Masahide Yamashita also formed a cooperative of Japanese growers that set a consistent price. Demand grew, the industry recovered, and lives were changed forever.

In addition to the history of the oyster, the film details Masahide Yamashita’s internment during World War II at Tule Lake, Calif., and his personal struggles to rebuild his business after years of confinement.

After the war, Japanese oysters were renamed Pacific oysters. Today, its shell is used as substrate to grow the native Olympia oyster.

Solomon says that although introducing a non-native species isn’t considered an environmentally-friendly choice, the Pacific oyster has cleaned up Puget Sound. The oysters filter water as they feed and each can clean up to 40 gallons a day.

She said they are the most widely cultivated oysters in Washington state and along the West Coast, from Alaska to Baja, Calif. They are also the biggest in size and, according to chefs and food critics, the most delicious.

Jerry Yamashita sold his Henderson Inlet oyster farm in southern Puget Sound to the Nisqually Indian Tribe in 2010. He still retains his historic tidelands in the Purdy lagoon. Solomon said the Yamashitas are considered shellfish icons among their peers.

“We want the film to be seen by as many people as possible,” Cornwall said.

“It has relevance to a lot of issues — the whole immigration issue, environmental challenges, a collapse of a species, and families. People take a lot of things away from it. For us, it makes it feel like we succeeded at some level.”

For more information, and to buy tickets, see http://buytickets.at/leapingfrogfilms/136715.

Leaping Frog Films’ website is at http://www.leapingfrogfilms.com/index1.html.

________

Jeannie McMacken is a freelance writer and photographer living in Port Townsend.