PORT ANGELES — The Cascadia Subduction Zone’s huge fault isn’t the only mover and shaker residents need to worry about, according to geologist Dann May.

The North Olympic Peninsula is riddled with earthquake faults, he said.

May, who spends summers in Port Angeles, told about 30 people at the Port Angeles Business Association on Tuesday morning that he began studying the Peninsula’s geology after he purchased property in Port Angeles, where he eventually hopes to live, and wanted to know more about its stability.

The subduction zone fault can create huge quakes — in the magnitude-9.0 range — which he said no building can withstand, no matter how good the codes are, but it only strikes on an average of every 500 years, according to a 2011 U.S. Geological Survey report.

“That quake will generate a tsunami that will reach us in 10 minutes,” May said.

“Every place with a place name with bay, canal or port is at risk.”

But such a quake isn’t likely to happen in the lifetime of anyone living today in Washington state, said May, adjunct professor at Oklahoma City University in Oklahoma City.

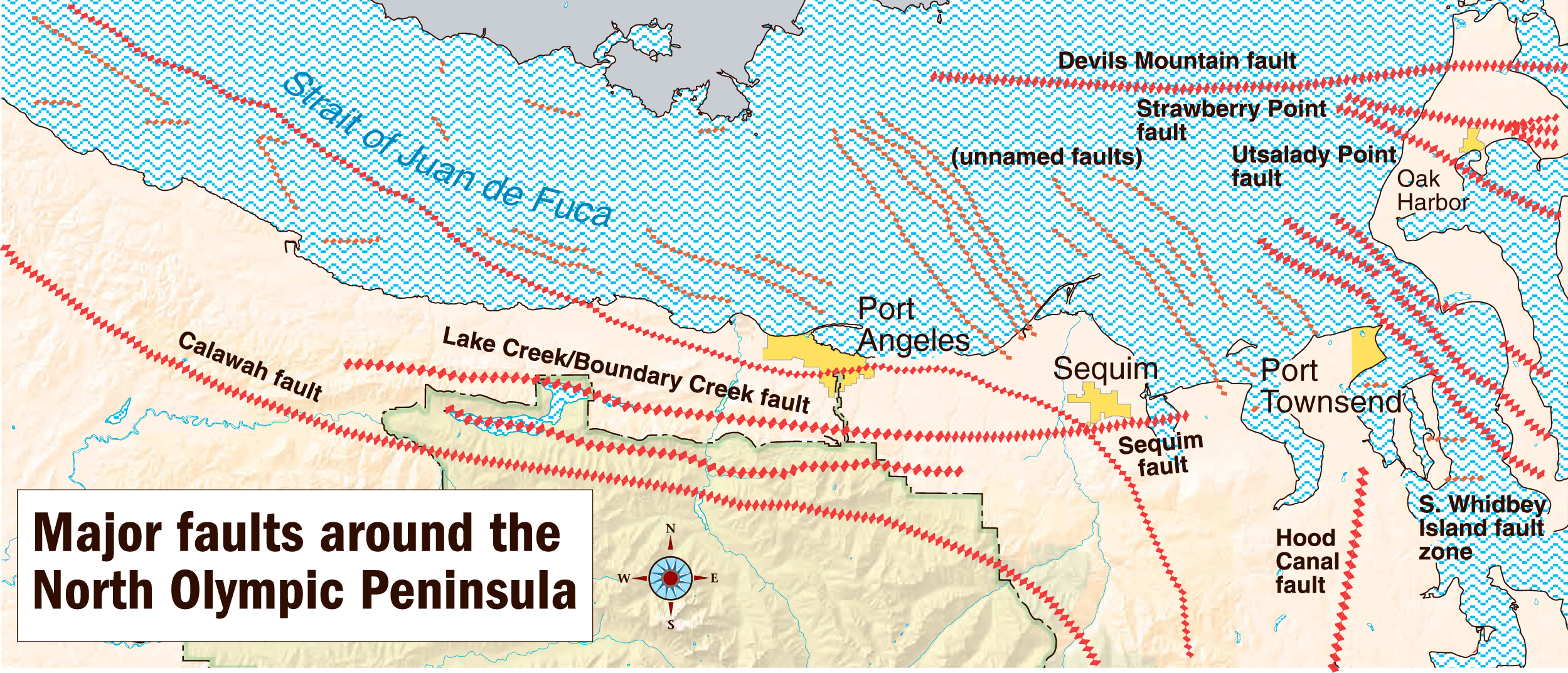

He thinks that of more immediate concern to those living on the North Olympic Peninsula are four main faults that run through the Peninsula and dozens of other faults in the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

The faults, which run east-west along the Peninsula, could generate earthquakes that could reach magnitudes of 6 or 7 — plenty large enough to do some serious damage to the region, said May, who also is the director for the Vivian Wimberly Center for Ethics and Servant Leadership at Oklahoma City University.

Buildings would be damaged but could possibly withstand such stresses, May said.

“We want our houses to withstand a 6 or a 7, maybe an 8,” he said. “No code will withstand a 9.”

Local faults are of the type called “reverse faults,” in which one block of land is being pushed up and over another block of land.

The four main faults have created four such blocks: Hurricane Ridge, Klahhane Ridge, Mount Pleasant and most of the bluffs and higher portions of Port Angeles and Striped Peak.

The faults are located in the valleys between each of those blocks of land. Lake Crescent is within two faults. One fault runs through Port Angeles, he said.

On the western face of the Olympics, each of the major river valleys is formed on top of a fault, which broke up the ground, making it easier for the river to dig its riverbed, he said.

May said present maps are incomplete, not showing exact areas of faults. The maps are correct within about 100 feet, he added.

“We need better mapping of active faults in Clallam County,” he said.

In Texas, where May spent six years studying similar faults for Standard Oil, such faults are associated with oil deposits.

The Olympic Peninsula formations are much younger, he said, and, with the exception of now-depleted deposits under Oil City, do not have oil.

Many of the lower-elevation faults are disguised by debris from glaciation or by vegetation, while they are easily visible at higher elevations, May said.

To check for fault lines, go to the Washington Interactive Geologic Map at www.tinyurl.com/PDN-Geology and zoom in on an area.

________

Reporter Arwyn Rice can be reached at 360-452-2345, ext. 5070, or at arwyn.rice@peninsuladailynews.com.