IT IS GOOD to use significant milestones to remind ourselves that life has risks, and we always need to be watchful.

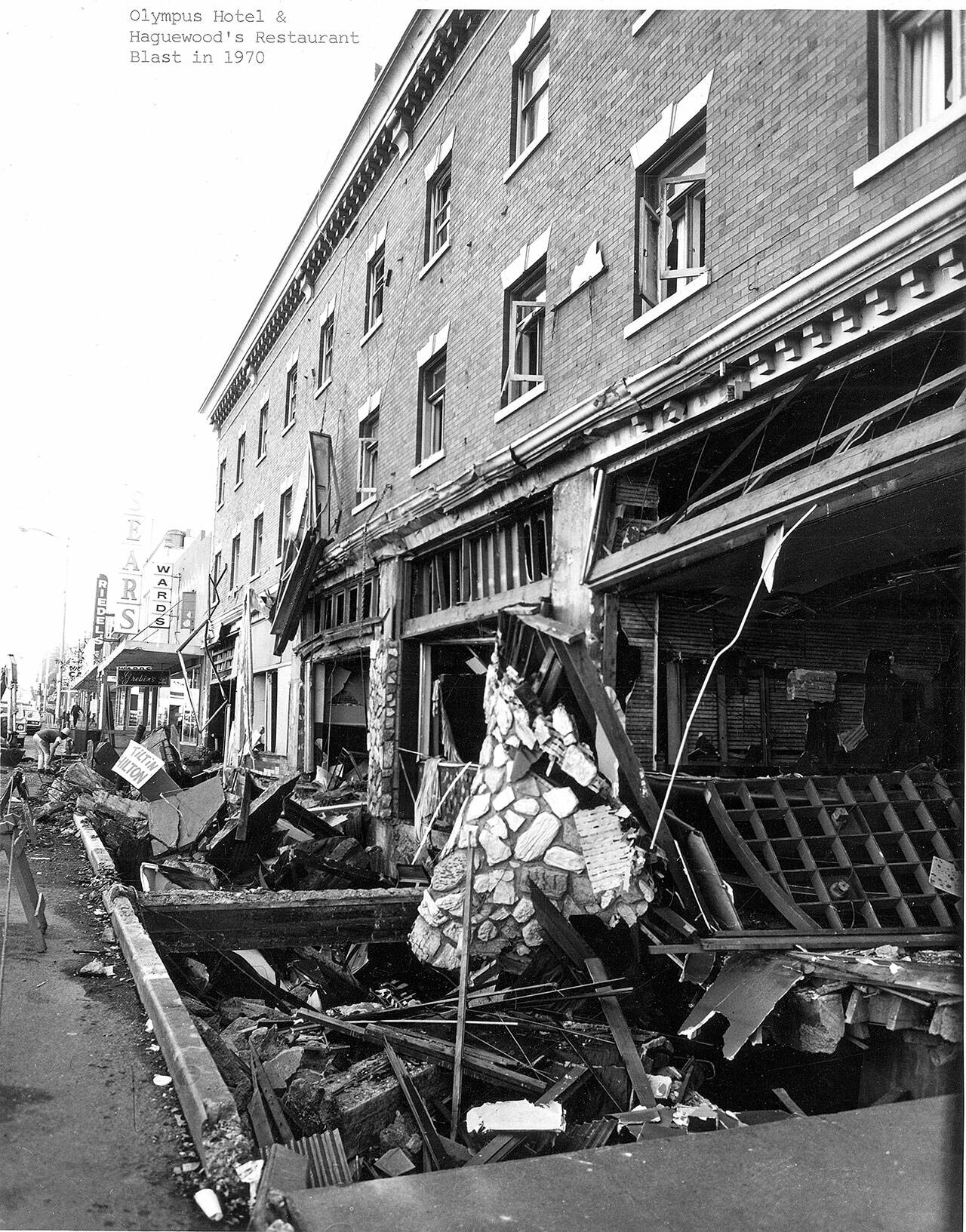

I say this because I noted this year is the 50th anniversary of an event that many of us vividly remember. On Thursday night, Sept. 30, 1971, a gas explosion ripped apart the four-story Olympus Hotel at 110 E. Front St. in Port Angeles. The blast also destroyed Haguewood’s Restaurant and Glamour-ella Health Spa. Both businesses were on the hotel’s street level.

There were 38 people injured in the blast. Miraculously, there were no immediate fatalities. Gene Martin, the most severely injured, was flown by the Coast Guard to Virginia Mason Hospital in Seattle, where he remained in a coma until his death 96 days later, Jan. 4, 1972.

Some inspectors believed gas leaked from a corroded pipe in the line that provided butane to local businesses. Other experts pointed to excessive pressure in the line. Either way, gas built up under the sidewalk, and a spark ignited it. The long-term result was Natural Gas Corp. of Washington ceased service in Port Angeles.

One survivor, Erv Schleufer, recalled that night. He was in Haguewood’s with three friends.

“I was the first to stand up and was looking straight out the window when I saw an orange flash outside and felt a stinging burn slap me across the whole front of myself,” he said. “It hurt all the way to the bone, and it threw me backwards onto the floor, where somehow I fell face down.”

Remembering the explosion is one thing, but we must never forget those who were impacted. Some injuries healed, and some did not. Some have fears they didn’t have before, while stress and mental problems overtook others. And some may still think about that moment every single day of their lives.

As we would expect, the courts were kept busy dealing with more than a dozen lawsuits representing 45 people seeking recovery for property and injuries. A parking lot now sits where the Olympus Hotel once stood.

The explosion was considered the worst disaster Port Angeles had ever experienced. However, it is not the only explosion the North Olympic Peninsula has experienced. Here is a sampling of the others:

Feb. 20, 1921

It turns out that 2021 is the centennial of another tragic explosion, which killed two young men. Lyle Davis and Voll Rice both lived on Lost Mountain. The exact story is unclear, but the two young men found two 3-foot cans of calcium carbide at an abandoned logging camp. It appears they had punctured the top of the cans and touched a match to light the fumes, but the explosion didn’t occur until they tossed the cans into a pool of water under the old shack they were exploring.

When the cans of calcium carbide hit the water, the mixture produced acetylene, and the previous lighting of the fumes ignited the acetylene, causing an explosion that blew the young men into the air. One died instantly, and the other died a few hours later. A flying board sheared the top off one boy’s head.

Lyle Davis’ younger brother was wary of the whole idea of messing with the carbide, so he was running from the area as the cans exploded. The blast knocked him to the ground and caused injuries that required medical care. He had to run 2 miles to his home before he could get help.

The physical wounds healed quickly, but the emotional wounds may never have.

Aug. 5, 1925

A pile of sulfur exploded on a Port Angeles wharf, blasting a large hole in the wharf and causing a fire. It took two hours to extinguish the blaze. In addition, 200 tons of sulfur fell into the harbor. The damage to the wharf was estimated at $1,700, equivalent to $26,000 today. I am curious why we had so much sulfur.

Aug. 8, 1948

Two young brothers died because of a freak accident, but we should call it what it really was: the collateral damage of war.

In 1943, the 115th Cavalry Squadron sought to lease land to use as a ground-to-ground combat range. The result: That land became the Port Angeles Combat Range and was located on Deer Park Road near Township Line Road. The range was used for tactical firing problems and short-range known-distance firing, using live munitions, including mortar and artillery shells. Occasionally, a shell would not detonate upon impact. In 1944, the range was declared excess.

Four years later, brothers Homer and Howard Swagerty were cutting pulp wood with their uncle on the former range. A 37-millimeter shell imbedded in the log exploded when their saw hit it. Howard, 13, died instantly. Homer, 11, died the next morning. The family was devastated for many years.

Immediately after the Swagerty brothers’ deaths, the Army de-dudded the area. Why didn’t the Army clean up the site before it was abandoned?

Nov. 20, 1967

A mysterious explosion jolted downtown Port Angeles. A pickup owned by Port Angeles Police Sgt. John Sweatt was found demolished behind the police station, which was at the corner of Front and Oak streets at the time. The blast ripped out the right side of Sweatt’s pickup. It also damaged an Olympic National Park truck, broke two windows in the police station and two windows in an office building across the street. Officer Virgil Bishop, who was in the station at the time, said he noticed the odor of dynamite.

Sweatt experienced another close call later when he got into his car and found three sticks of dynamite with a lit fuse under his seat. Sweatt grabbed the dynamite and took it apart. A group of young people were arrested for the crime.

History can help remind us that there are risks in life. Be careful out there.

________

John McNutt is a descendant of Clallam County pioneers and treasurer of the North Olympic History Center Board of Directors. He can be reached at woodrowsilly@gmail.com.

John’s Clallam history column appears the first Sunday of every month.