WHEN YOU ARE traveling east of Port Angeles, you’ve likely seen the street sign for Lake Farm Road. How did that road get that name?

Suitable soil for farming and gardening was a priority for the Clallam County early settlers. Most of the Olympic Peninsula was thick forests and dense brush.

Homesteading was arduous work, but the fruits were worth it. After much work, a homesteader could gain title to the land.

Homesteading required a simple three-step process. First, a head of household would file an application. Second, they had to live on the designated land, build a home, make improvements and farm it for a minimum of five years. Third, they could file for a deed to the land after five years.

Finally, after years of hard work, the time arrived for homesteaders to make proof of residence and secure the title to their claims.

Natural resources were readily available for building homes and making other improvements; however, finding land for farming was a bit more difficult. Clearing brush was one thing, but removing old growth trees and their stumps was difficult. So, a shallow lake seemed almost too good to be true. Drain the lake and, presto, you have a farm.

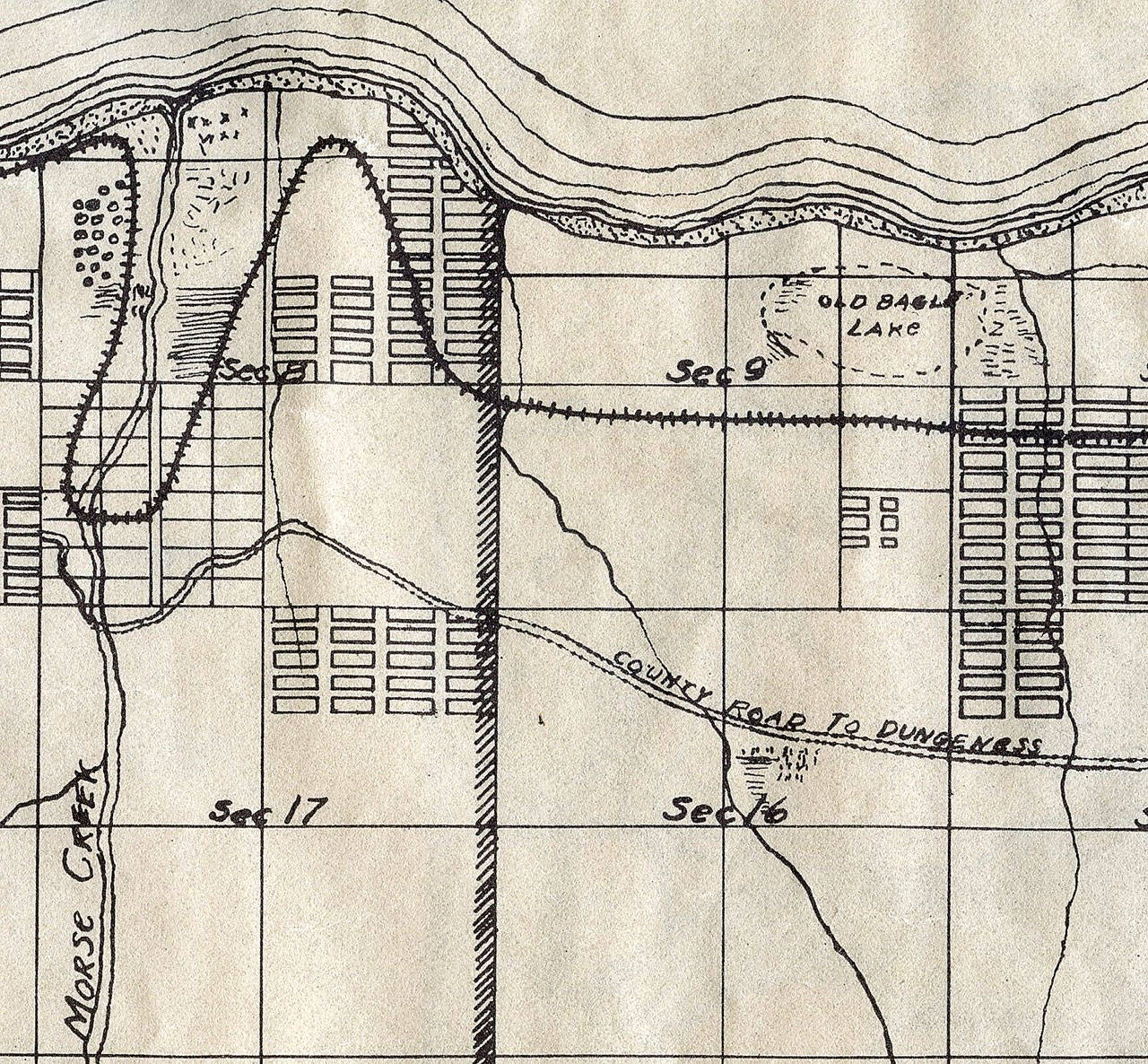

John Bagley homesteaded this land in 1870. Bagley Creek also is named after him.

When he realized he had a large lake near the bluff’s edge overlooking the Strait of Juan de Fuca, he devised a plan to drain Bagley Lake and use the lakebed for farming. The lake was not deep and covered about 200 acres. It was formed mostly from rainwater, and it was swampy and likely stagnant.

Bagley’s plan

His plan was simple enough. First, dig a tunnel — maybe 200 feet long — from the beach to a point near the lake. Second, dig a well down to the tunnel. Then, dig a ditch from the lake to the well to drain the lake.

The tunnel, still visible from the beach, was started about 10 feet above high tide levels; it was about 20 feet wide and 30 feet tall. Bagley and his hired help would move the dirt with a wheelbarrow, dump it out the mouth of the tunnel and let the tide remove the spoils.

At that point, many of you will recall the local legend that Chinese laborers were hired to dig the tunnel, which has been referred to as “Chinaman’s Cave.” As the legend goes, when the lake water broke through, many Chinese laborers were washed away to their deaths. While this provides good fodder for storytelling, there is no documentation that anything like that happened. I relegate this story to myth; there was no sudden breach of water under Bagley’s plan.

We know the old saying, “If it’s too good to be true, it probably is.” Well, Bagley drained the lake too fast and exposed a lot of peat and decaying vegetation that had been on the bottom of the lake. The sediment was 2 to 3 feet thick and dried like clay, requiring steel tools to break it up. It ended up being too hard to level out for farming, and as a result, the lakebed was left to develop into brush and small alder trees.

The land passed through other owners over the years, including Silas Virginia, his wife and seven children. They built a log cabin on about 2 acres of clear land on the east side of Lake Farm.

In 1887, Lake Farm was purchased by Charles Wintworth (Wint) and Cynthia Stewart Thompson from William Delanty.

Wint and his family initially lived in the old log cabin built by the Virginias.

Charles and Cynthia traveled from Nova Scotia, Canada, to Port Angeles through San Francisco. There is a bit of local trivia here. When the Thompsons were leaving San Francisco, they missed their steamer, the Brother Jonathan. The Brother Jonathan was lost, along with all aboard, off the coast of Crescent City, Calif., on July 30, 1865. Those souls lost included Victor Smith, founder of Port Angeles.

Wint’s son Lewis (Lew), born Jan. 13, 1877, in a small shack in Dungeness near the mouth of Cooper Creek, was 10 when he first saw Lake Farm. He was kind enough to share his memories about Lake Farm in 1972.

Like Bagley, Wint also had a plan. He knew how to develop those rough lands, and he started by cutting down the brush and small trees. The next summer, after the brush and trees had time to dry, he set fire to the brush. That resulted in the chunks of peat also burning. The addition of the ash improved the soil’s fertility.

When the fire had burned down and exposed wet peat, it was spongy enough that, if one jumped on the ground, it jiggled up to 20 feet away.

Wint’s initial effort had managed to level about 80 acres of good farmland. In 1888, they managed to plant their first crop of oats, which they used for hay. Lew remembered that the oats grew to about 5 feet tall, and the stalks were a half-inch in diameter.

The lowest part of the lakebed, about 10 acres, needed further draining, and Wint dug deeper ditches to the tunnel to drain it. Then, it could also be put into farm production.

The farm continued to be productive. In the winter of 1900, severe northeast gale-force winds tore the roof off the barn, and about 50 tons of hay ended up covered with a foot of snow. Besides the damage to the barn, the Thompsons may have lost $500 in income from the sale of hay; it was a significant loss in 1900.

The Thompsons remained on the Lake Farm for many years. Lew died Feb. 20, 1974.

Today, draining a lake is almost inconceivable. In those times, it was considered innovative rather than an environmental misfortune. But before we get too self-righteous remember, there will be objectionable things in our own times we do not see. Collectively, our memories need to be recorded somehow to best understand the past.

________

John McNutt is a descendant of Clallam County pioneers and treasurer of the North Olympic History Center Board of Directors. He can be reached at woodrowsilly@gmail.com.

John’s Clallam history column appears the first Sunday of every month.