LIGHTHOUSES HAVE LONG served as a navigational aid for maritime pilots at sea or on inland waterways. Lighthouses marked dangerous coastlines and safe passages. The number of lighthouses has declined due to the expense of maintenance, and have become uneconomical since the advent of cheaper and often much more effective GPS navigational systems.

To be a lighthouse keeper was a very noble and important vocation which required diligence and dependability. It was important to keep a lighthouse operating during the worst of storms under the worst of personal conditions.

The Strait of Juan de Fuca may be deep and wide, but entering it from the Pacific Ocean proved to be challenging. The mouth of the Strait was known as the “ship’s graveyard” because of all the vessels that went down. Tatoosh was an important spot for a light and a fog horn, which began operation in 1857.

John Merrill Cowan was born in Redwood City, Calif., on Oct. 12, 1862. He married Mary Emily Mosher, a member of a prominent Oregon family, in 1886. They had a total of eight children.

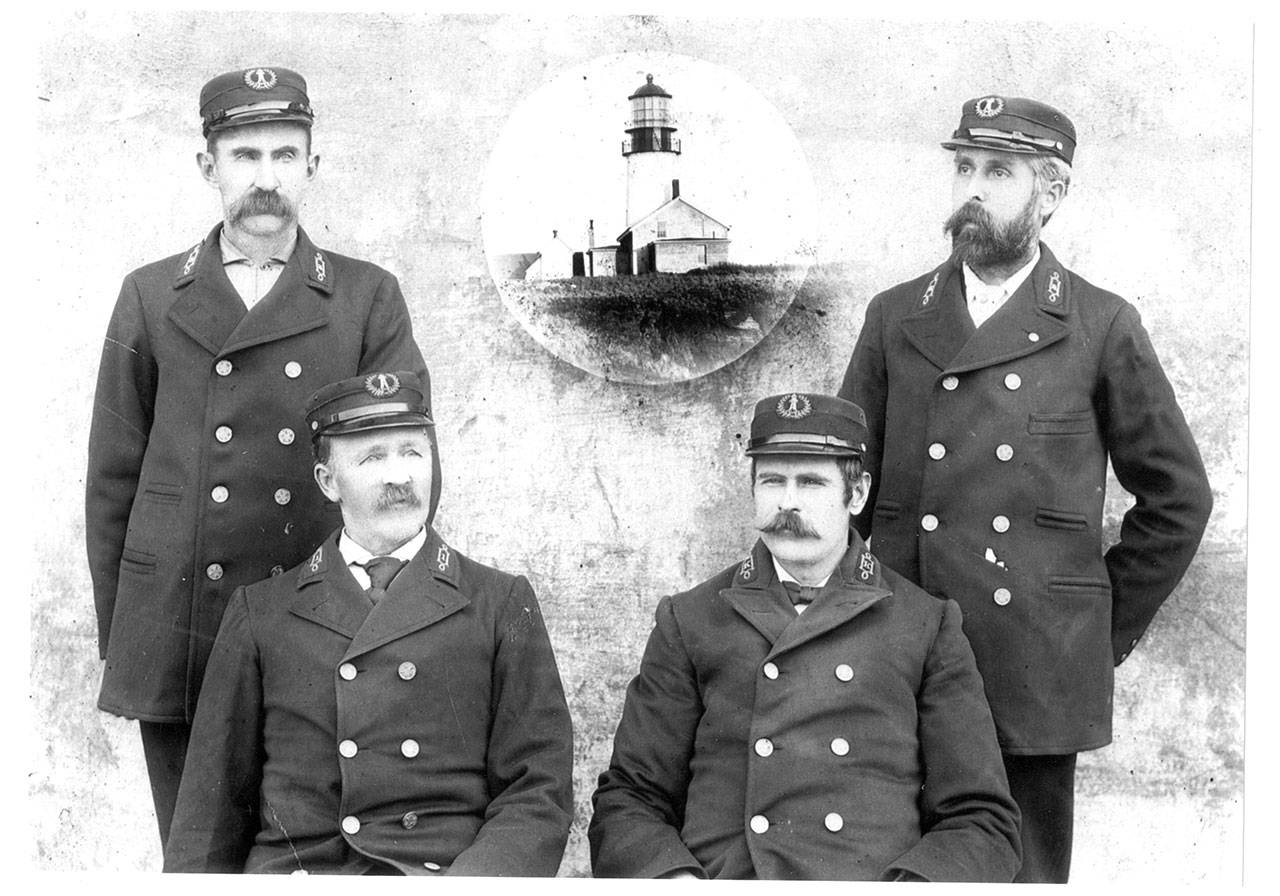

John entered the Lighthouse Service on March 9, 1893. He started his duties at two Oregon lighthouses, Coquille River and Heceta Head. On May 16, 1900, the Cowans arrived at Tatoosh Island with their seven children. Their eighth child did not arrive until 1904. Tatoosh Island became their home for the next 32 years.

Tatoosh became John’s 17-acre empire, but difficulty and sacrifice were soon evident. Tatoosh Island is about 2,200 feet offshore. The nearest town, Neah Bay, was a 7-mile boat ride.

On Oct. 27, 1900, Nils Nelson, second assistant keeper, and Frank Reif, the timer, left that morning for Neah Bay. It was stormy weather. They never arrived in Neah Bay and no trace of them was found.

Regular communication used Makah mail carrier canoes which made the 7-mile trip from Neah Bay twice a week. If the weather was bad, the deliveries were lobbed onto the shore. Even when the island got a piano it was delivered in a dugout canoe.

It is very evident that their children’s education was very important to the Cowans and it came with a price and great sacrifice. Each fall the children boarded a tender and were transported to Portland, Ore. They lived with their aunt Winifred Mosher during the school year. In the spring the children were brought back to Tatoosh to a joyous reunion. School was not free. It took most of their money to pay the cost of clothing and schooling their children. This was the situation for 10 years.

Mary Cowan stated, “But we’ve lived to be proud of our children. We’re glad we gave them their chance; and the proudest day of our lives was that on which we learned that our son Theron had passed successfully his coast guard examination for warrant boatman, with grades above 200 other applicants.”

The Cowans were also proud of their son, Forest. On Sept. 1, 1907, Forest was appointed acting third assistant keeper of Cape Flattery Light Station. He earned a salary of $550 per year. In 1907 the average worker made between $200 and $400 a year.

During his 32-year tenure John Cowan was credited with saving five lives. He launched the lighthouse boat in gale force winds and rescued two Makah mail carriers whose canoe had capsized. In another storm he rescued a weather observer from drowning. The last two he rescued came at a sorrowful cost.

On Feb. 18, 1911, five Tatoosh workers launched a boat for a trip to Neah Bay. Forest Cowan was an assistant lighthouse keeper. Mr. and Mrs. George L. Talmadge, M. Waddell, and I. D. Spoonemore were members of the Navy wireless telegraph team. The Talmadges had been married only three months at this time.

The British tug Lorne was anchored near the island waiting to bring the people to Neah Bay. The tug radioed the island to prevent the group from launching, but the message was received too late.

It appeared to those onshore that the boat had cleared the surf safely. Then three large waves in succession broke over the boat. Their boat filled with water and became unmanageable. It was capsized by heavy swells. Forest Cowan was washed overboard first. The other four clung to the boat as long as they could.

John Cowan launched out in the lighthouse boat to attempt a rescue. He had to steer with one hand and bail out water with the other. John maneuvered the boat to the last two men clinging to the capsized boat. He was able to save George Talmadge and I.D. Spoonemore. George Talmadge had clung to his wife’s hand as long as he could, but hypothermia was taking its toll. Mrs. Talmadge, Forest Cowan and M. Waddell were lost. The tug and the rescue boat searched the waters for an hour. The bodies were never found. Cowan bravely saved two men but could not save his own son.

Spoonemore and Talmadge were put aboard the Lorne where the crew provided first aid. Then they were transported to Neah Bay for medical attention.

In 1921 high winds of 70 mph wreaked havoc on chimneys and roofs. Cowan was blown end over end for about 300 feet. He had to cling to the grass and crawl back to the house.

An unusual aspect of life on Tatoosh happened when a large seagull flew into the bedroom window of the Cowan’s youngest daughter, Winifred. The seagull seemed to adopt her and remained with the family for many years like a member of the household.

Sometime in the 1930’s a bull was blown across the island and disappeared into a ravine near the center of the island. The ravine led out to sea via caves. The Cowans thought the bull was dead, but it swam back to shore the next day. Extra feed for that one.

On Oct. 12, 1932, John Cowan had reached the mandatory retirement age of 70. He retired after 39 years of duty in the U. S. Lighthouse Service. With the money they had saved over the years the Cowans purchased a home in Carlsborg within earshot of the Dungeness Lighthouse foghorn. He picked Carlsborg as home because, “I picked a place where I could hear a foghorn, but that’s as close as I want to be to it.”

Sadly, John Cowan did not enjoy his retirement very long. He became ill soon after his retirement and died in 1934.

________

John McNutt is a descendant of Clallam County pioneers and treasurer of the North Olympic History Center Board of Directors. He can be reached at woodrowsilly@gmail.com.

John’s Clallam history column appears the first Sunday of every month.