FOR THE PIONEERS of Clallam County, life was hard. Living was difficult. Getting enough food was not easy. Traveling was treacherous. You most likely were on your own when there were medical needs.

The land was tough enough. It was even worse when you had to struggle against other people.

Daniel Webster Pullen was born on May 24, 1842, in Maine in a Quaker family. Dan’s father died in 1849 from scarlet fever. Scarlet fever is a form of strep. Regrettably, he left behind a wife and eight children ages 5 months to 12 years. Scarlet fever also left several of those children deaf.

Daniel ran away from home at age 14. In 1856, 14 years of age was old enough to take on adult responsibilities. The combination of lower living standards, greater exposure to hazards, heavier labor, and poorer medical care resulted in an average life expectancy of 39 years in that era.

Daniel sailed to Panama where he crossed the isthmus and then sailed north to Puget Sound. There he worked in logging camps driving ox teams.

Daniel was industrious and eventually bought a schooner. With that he sailed around Cape Flattery trading with the native peoples and settlers.

By 1870, Daniel had earned enough money to set up a trading post at La Push. Daniel managed to prosper. In 1881, it was reported that Daniel was the wealthiest man in the area. He invested in land throughout the area.

On February 28, 1881 Daniel married Harriet Matilda Smith who was 18 years younger than him.

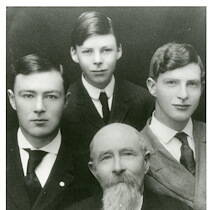

Their first child, Mildred, arrived in 1882. Followed by Dan (1885), Royal (1887) and Chester (1889).

Together they built a beautiful home in La Push overlooking the ocean and native village. Their house was called the Pullen Mansion. For the first several years of their marriage, they lived a life of wilderness luxury. They had many of the best amenities of the day.

But the good life would soon begin to crumble. On July 8, 1882, Pullen filed a preemptive claim on land in La Push. The Preemption Act of 1841 permitted settlers who were living on federal government owned land to purchase up to 160 acres at a very low price before the land was to be offered for sale to the general public. On July 9, 1883, Pullen finalized his claim.

On Sept. 10, 1884, the Indian Agent in Neah Bay reported to the Commissioner for Indian Affairs that Pullen’s claim was on land occupied by an Indian village. The Commissioner began an investigation.

The remoteness of the claim made an investigation difficult. But the Indian Service was persistent in its examination. Even though he had built a house, on Oct. 12, 1887, Pullen’s claim was canceled. Pullen was granted a hearing on Dec. 3, 1887. Various factors caused delays until Nov. 6, 1890, when testimony began at Port Townsend before the Commissioner.

The result of the hearing was, again, the cancelation of Pullen’s claim. The reason given was that the tract of land was occupied by the native peoples prior to the time Pullen made his settlement and improvements on the land.

Pullen appealed and the decision was reversed on Sept. 22, 1891. George Chandler, First Assistant Secretary of the Department of the Interior, reviewed the facts. Citing treaties, government Indian policy and a preponderance of testimony regarding native occupancy long before Pullen arrived, the last decision was reversed, and Pullen’s claim was canceled. Pullen continued to fight the decision.

Stepping back a bit, around 1885, Seth Baxter and the Washington Fur Company purchased the store and Pullen became an employee.

Soon there is a dispute between Seth Baxter and Daniel Pullen. No one is certain when it began, but it involved Harriet. It seems that Baxter disliked Harriet. He felt she “put on airs.” That is when a person acts superior to others.

Baxter claimed that between Dec. 1, 1886, and June 1, 1892, Harriet was removing goods from their store for her own use and not paying for it. Dan, of course, sided with his wife.

So in 1892, Baxter and the Washington Fur Company sued Pullen in Clallam County Superior Court for $18,704.51. Baxter claimed that amount of goods that were taken. To give some perspective, Baxter’s claim would be equivalent to $590,000 today. So, this lawsuit was a big deal. In fact, it was the largest in the state at that time.

Daniel was very deaf during this time frame. He needed Harriet to aid in the business. This made Harriet a key witness during the trial. Harriet was on the witness stand for a week. The cross examination was unusually long (four days) and it was estimated that Baxter’s attorney, Charles F. Munday, asked Harriet 4,500 questions. As trying as it was, Harriet maintained her credibility.

On June 26, 1893, the jury sided with the Pullens returning a verdict for the defense.

It was noted that the plaintiffs and the defense both had two attorneys.

Three experts were used and over 300 exhibits were placed into evidence. The trial cost nearly $100,000.

All that for an $18,704 claim. It appears that only the attorneys profited from the trial.

For the Pullens, one trial had ended successfully. But the land issue persisted. By March 1893 the matter was basically over. The Pullens would lose their home and the land it sat upon.

During this time the Pullens had sued the Indian Agents and Seth Baxter for the harm caused by them. These suits were to no avail. The financial cost was devastating. The Pullens were forced to mortgage all their holdings. It was a very difficult time for the Pullen family.

By 1897, the Pullens were broke. For a year newspapers around the state ran short filler articles saying Daniel had “suddenly become insane” and “left his home and has not since been seen or heard of. It is believed he has committed suicide.” It was not true. Daniel was very much alive.

For Harriet, the loss of income and prestige was too difficult to bear. She wanted to start over in Alaska. There was a gold rush going on.

Daniel, being 55 years old, was not interested in starting over again. In the fall of 1987, Harriet and Minerva Troy (of Port Angeles) boarded the steamer Rosalie and sailed for Skagway, Alaska.

Daniel left the Quillayute Valley and went to work for a Pope & Talbot logging camp near Port Gamble. Their sons stayed with Daniel until later when they reunited with Harriet in Skagway. Mildred was sent to the Ellensburg Normal School.

Around 1902, Daniel left Alaska and went to Kent.

Daniel died in Seattle on Aug. 14, 1910. His body was buried in the Quillayute Prairie Cemetery.

I think it is important to remember that everything has a cost.

Plus, it seems nature can be easier to deal with than other people.

________

John McNutt is a descendant of Clallam County pioneers and treasurer of the North Olympic History Center Board of Directors. He can be reached at woodrowsilly@gmail.com.

John’s Clallam history column appears the first Saturday of every month.