LAST MONTH I started telling the story surrounding the “Lady of the Lake.” A woman’s body had been found floating on Lake Crescent. The body itself was unidentifiable. All that law enforcement had was a dental plate and lots of theories. To serve justice they needed to know who this woman was.

It was the first body ever found floating in Lake Crescent. She quickly became known as “The Lady of the Lake.” It was a reuse of the name of a local boat. In 1891 a small steamboat was brought to Lake Crescent. It could carry a few passengers. It plied the lake’s waters for many years. It was easy to adopt the same name for our victim.

Almost immediately it was thought the body was that of Marion Frances Steffens of Chicago. Steffens had disappeared in the Olympics in September 1939. Based upon the body’s description and the clothes Steffens’ mother thought is was her daughter. Some details made her hesitate a bit.

Prosecutor Ralph Smythe was not convinced the details were conclusive enough to identify the body as Steffens. The County Doctor, Dr. Kaveney, agreed. It was known that Steffens had suffered a fractured neck vertebra. The victim had not.

Hope of a quick identification had faded. Soon, all the rope, clothing, blankets, and other evidence was turned over to the FBI in Seattle. Weeks past. Then months. Still nothing to identify the body was found.

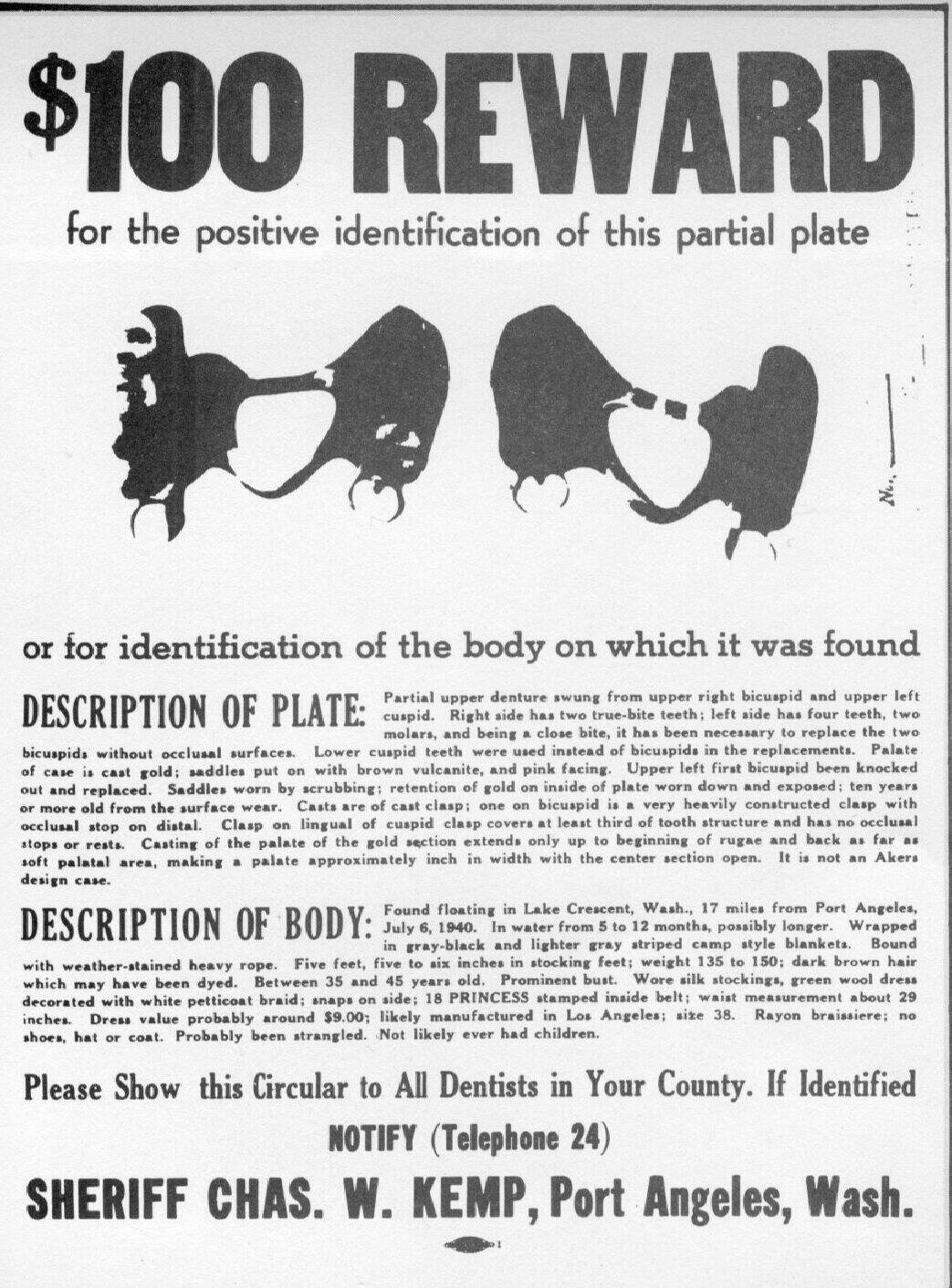

Using a photograph of the dental plate, Sheriff Kemp and Prosecutor Smythe had 15,000 circulars printed and they mailed them to dentists around the country. This was good old fashioned investigative work. Disseminating inquiries to the right people was not easy in 1940.

In our current context you would think of the circulars as your social media and the Post Office as your search engine.

Investigators did not sit around and wait for responses to their circulars. They also looked at small details. They saw that prior to her death, her hair had been styled. This lead to the possibility that she was working at the time of her death. On one foot they found a bunion. That indicated that her job kept her on her feet. They concluded she may have worked in a laundry or as a waitress.

Edgar Thompson, secretary and treasurer of the Culinary Alliance, compiled a list of names of several people who had dropped out of their organization during the timeframe of the murder.

One name on the list was peculiar. Hallie Illingworth was no longer on the organization’s list. And she apparently left without taking a union transfer or withdrawal card.

Investigators at last had a serious lead to investigate. Investigators located Hallie’s sister, Lois Bailie, in Walla Walla. Lois stated her sister had been missing since a few days before Christmas, 1937. Her sister also had a upper partial denture and an agonizing bunion on her right foot. This information was very helpful.

Lois had more important information. According to Lois, Hallie had a husband named Monty. Montgomery J. Illingworth and Hallie Strickland were married by a Justice of the Peace in Port Angeles on June 16, 1936. 18 months later, Hallie was missing.

Monty had claimed Hallie walked out on him for a naval officer and was living in Alaska. These claims would be difficult to dispute during this period of time. People could easily move to Alaska and vanish if they wanted to.

This information only solidified the resolve of the investigators. The pieces were coming together.

Investigators located another of Hallie’s sisters, Mrs. James Johnson, in Vancouver. More pieces to the puzzle fell into place. Johnson had a postcard from Hallie dated Dec. 21, 1937. This was the last time anyone had heard from Hallie. Johnson was also able to lead investigators to Hallie’s dentist in South Dakota.

Dr. A. J. McDowell of Faulkton, S.D. was able to identify the dental plate as his work. Investigators were now certain that the body found floating in Lake Crescent was Hallie Illingworth.

Closer to home, investigators located Jessie Hudson at a lumber camp cook house in Lake Pleasant. Jessie Hudson was a friend of Hallie and added more to Hallie’s story. She claimed that Hallie and Monty were intensely jealous of one another and that resulted in constant fights. Her recollections also linked Monty with a local woman named Elinore Pearson.

Possible motives for the murder were coming to the surface. More than one person had heard Hallie say that if they did not separate one of them would kill the other. The owner of the apartment building where they were living heard them fighting. He entered their room and found Monty standing over Hallie. She was on the bed moaning in pain.

In 1938 Monty had been granted an uncontested divorce from Hallie. That opened the door for him to marry Elinore Pearson.

So far, all the evidence pointed to Monty as the murderer. Investigators located Monty living in Long Beach Calif. He was living with Elinore Pearson. He gave investigators some confusing statements.

Monty claimed that on the night of Dec. 21, 1937, he had gone to a party with his friend Tony Enos. He came home drunk and boisterous. He said Hallie was angry and left. He also said Hallie swore she would never return.

Tony Enos was located. Tony confirmed the party and the date. Tony also said he saw Monty the next morning and Monty told him he was taking Hallie to the Port Ludlow ferry. Now there were three different stories.

The current Clallam County Prosecutor was Max Church. Ironically, Max Church had been Monty’s attorney. Max spoke with Mrs. Harry Brooks who was the owner of a general store near Monty’s home. She still had a piece of the rope Monty had borrowed just before Christmas 1937.

There was enough evidence to arrest Monty for murder on Oct. 24, 1941. Oh, by the way. The last installment of this story will be next month.

________

John McNutt is a descendant of Clallam County pioneers and treasurer of the North Olympic History Center Board of Directors. He can be reached at woodrowsilly@gmail.com.

John’s Clallam history column appears the first Saturday of every month.