EDITOR’S NOTE: Due to a production error, John McNutt’s Dec. 6 column did not run in its entirety. Here is the complete submission along with two new images.

AS 2020 COMES to a close, one thing is certain: It has been a peculiar year. We can’t see, yet, the affect the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) will have on us in the long term.

We are all citizens of our time and place. We are all products of the influences upon us — influences such as our friends, where we were born, the education we received, the media services we listen to and the theological or atheological tribe we associate with.

While we are experiencing the joys and travails of our immediate circumstances, we also need to consider what our collective and individual memories will be. We won’t remember this time clearly unless we somehow record them and the impact it had on us. For a while, our history calendar will remember things in reference to before, during and after the pandemic. It is important to make some record of those significant times and events through which we live and die.

Amy McIntyre has been doing just that. Amy is both artist and the executive director of the North Olympic History Center. McIntyre, a documentary photographer, originated a project of her own earlier this year called “Any Port in a Storm: Pandemic Sundays in Port Angeles, Washington.”

For 16 straight weeks, she captured moments of life — or quietude — in all corners of the city. The U.S. Library of Congress selected Amy’s “June 28, 2020” photograph for its “COVID-19: American Experiences” gallery and permanent collection.

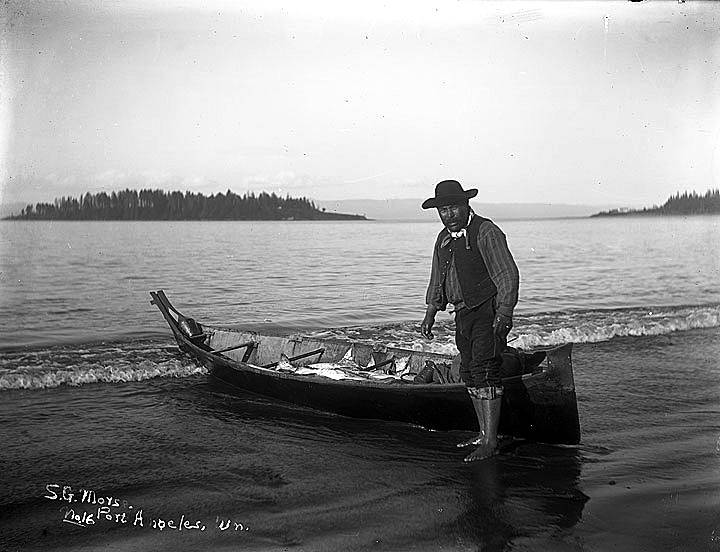

In a much different time, Samuel Gay Morse captured moments in the life of the Makah people through photography.

Morse was born on Aug. 10, 1859, in Pescadera, Calif., which is in Santa Cruz County. Political uncertainties led the Morse family to move north to Washington. They first landed in Victoria. From there, they boarded the steamer Eliza and came to Port Angeles. From Port Angeles, they traveled east by native canoe to homestead at the mouth of a creek that would later bear their name — Morse Creek.

Morse grew up in Port Angeles and was knowledgeable of early Clallam County history and native lore. He was acquainted with the S’Klallam, who inhabited villages nearby.

In his late teens and early 20s, he worked as a land survey chainman, helping subdivide a township southwest of Port Angeles.

Morse’s cousin, Davis W. Morse Jr., was inclined towards entrepreneurial enterprises and was business-minded. Sam, on the other hand, was equally ambitious but inclined towards politics. Sam was elected to Port Angeles’ first Chamber of Commerce. He also served four terms as sheriff and five years as assessor.

By using his political connections, Sam earned a nomination from President William McKinley to serve as what was called then an Indian agent for the Neah Bay agency. The U.S. Senate confirmed Sam’s nomination.

An Indian agent had several responsibilities: they helped settle disputes; performed marriage ceremonies; supervised reservation teachers and employees; and represented the interests of the Makah to the federal government.

Indian agents also had to enforce agency rules and regulations. Sam was lenient in that regard. He had a reputation for fair dealing and a kindly disposition. He allowed potlatches as long as no whiskey was involved and sanctioned native doctors as long as they didn’t charge for their services.

Sam knew the First Peoples in this area had a rich and important history. He was also aware of the impact the United States was having on their life and culture. So, he worked to help preserve their history through photography.

There were commercial photographers at this time who viewed the Native Americans as an exotic marketable subject matter, but Sam wasn’t motivated by the marketplace.

Sam had a special dedication to this work. The invention of gelatin-coated dry plates significantly reduced the necessary exposure time. As a result, documentary photography became more feasible. But it was still hard, physical work to carry fragile glass plates and heavy cameras from one spot to another.

He was self-taught in photography and always referred to himself as an amateur photographer; yet, he built up an impressive body of work. It has been written of Sam that, “he created an impressive body of Indian portraiture and documentation, in an unpretentious style not previously employed by other photographers of the Indian people of Washington.” Instead of posing and staging, he photographed people and places where and as he found them.

Sam would not have been considered extraordinary. Yet he seemed to be in the right place at the right time. His friendly relations with the Makah enhanced his photography.

In 1903 Sam wrote, “I have known most of these people here for over 30 years, and I want to assure you that I have a warm spot in my heart for them.”

Sam had an understanding of the importance of his photography. His entire work totaled some 1,000 negatives and prints. In 1917, he sold his entire body of work to the Washington State Historical Society for $300. He wanted his work preserved for posterity. I have no doubt that he could have made far more money selling prints on the open market.

Samuel Morse died of heart failure on Nov. 27, 1921, at age 62, and his images remained relatively unknown except to a few until 1969, when the Washington State Historical Society made a traveling exhibition of his work of the nearly forgotten photographer.

Other photographers, such as Edward S. Curtis, were far more prominent. But, Sam came from a Clallam County pioneer family and didn’t venture much beyond the Olympic Peninsula. He spent his life here without much material reward. As a photographer, though, he made a unique contribution to our heritage.

What will we remember when these unusual times have ended? There will be an army of professional historians who will share their interpretations with future generations. What about you? What will you be able to tell future generations?

I will give you two references which should be enriching. First, search the Washington State Historical Society’s collection for Samuel G. Morse items. Second, find the book titled, “Portrait in Time,” which is published by the Makah Cultural and Research Center.

Enjoy!

________

John McNutt is a descendant of Clallam County pioneers and treasurer of the North Olympic History Center Board of Directors. He can be reached at woodrowsilly@gmail.com.

John’s Clallam history column appears the first Sunday of every month.