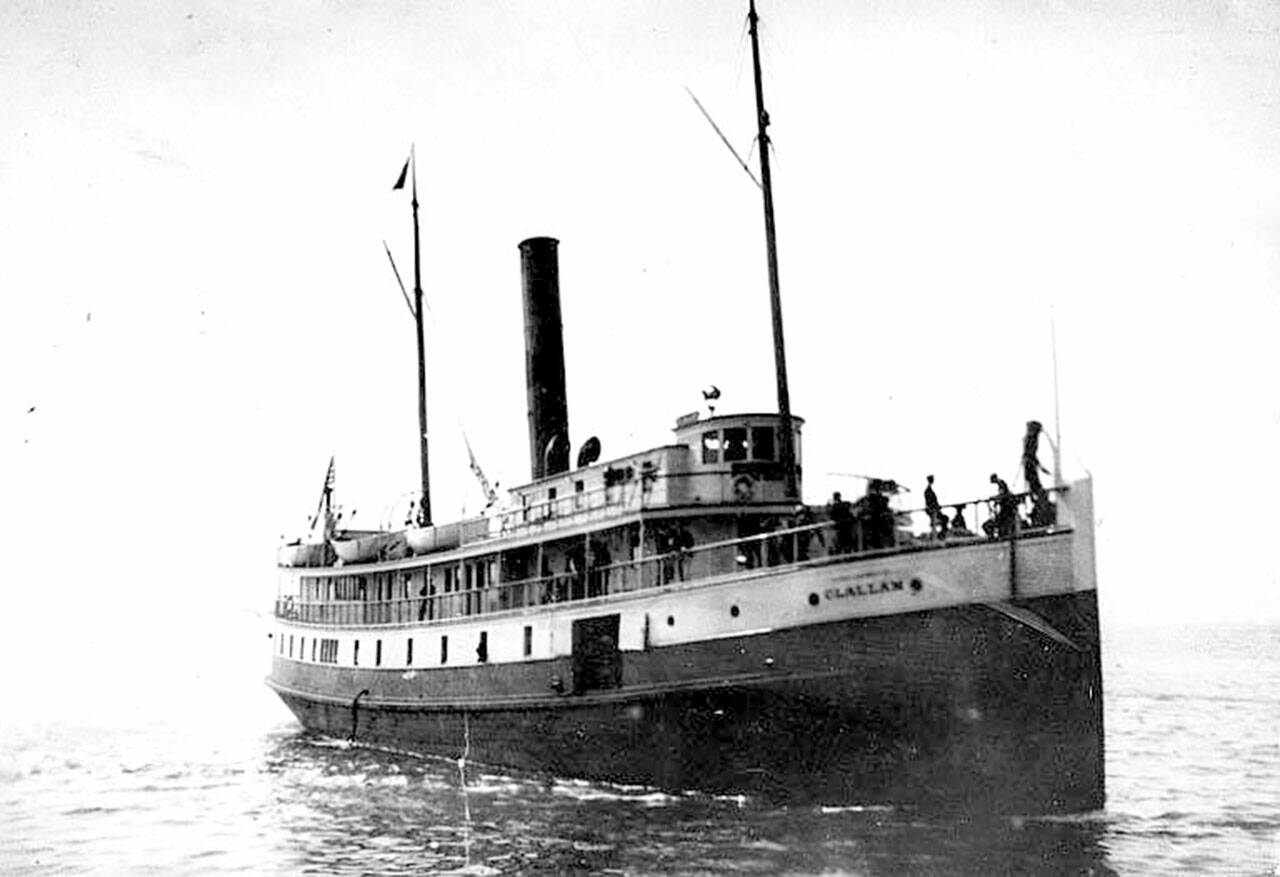

IT SEEMS THAT people have a fascination with shipwrecks. Unlike other disasters, shipwrecks leave behind a monument to the that we can see, explore, and analyze. They are bad events that make for intriguing stories. The steamship Clallam gives us one such story.

Launched on April 15, 1903, the SS Clallam was a 657-ton, 168-foot wooden-hulled steamship built in Tacoma owned by Puget Sound Navigation Co., now known as the Black Ball Line. She had 44 elegant staterooms, a cruising speed of 13 knots and carried six large lifeboats.

Sailors and fishermen know the sea is dangerous. Over the centuries, many superstitions have been born around safety and luck on the sea, and to some superstitious sailors, the Clallam was a jinxed ship.

When the U.S. flag was first unfurled it was upside down, the universal distress signal. When the blocks were knocked away during the launch, the Clallam slid down too quickly, and the bottle of champagne missed the bow and failed to break. Old sailors predicted disaster would strike the Clallam within a year.

The Clallam’s master and pilot was Capt. George Roberts, and he was a very capable skipper. He was one of the founders of the Black Ball Line and had navigated the inland water for three decades. The Clallam was the fastest and most modern ship in the fleet and was put on the Seattle to Victoria run. This run included a stop in Port Townsend.

Friday, Jan. 8, 1904, was a normal day. The Clallam was loaded with cargo and passengers in Seattle. Sheep were often carried as freight to Port Townsend, and the bell sheep, trained to lead a flock onto the ship, refused to board. Some saw it as a premonition of disaster.

The Clallam departed Seattle at 8:15 a.m. bound for Port Townsend. The voyage took three uneventful hours.

After an exchange of freight and passengers, the Clallam departed from Port Townsend at 12:15 p.m. The waters were calm, but that changed about an hour after the ship cleared Point Wilson.

Now, the Clallam had to battle heavy seas and gale-force winds from the west, carrying a mix of rain and snow across 35 miles of open water.

Soon, water was entering below deck, maybe through an open deadlight (a shutter over a porthole). But they pushed forward because Victoria Harbor was in sight. But hope of safe harbor vanished at about 2:30 p.m. Almost 5 feet of water had filled the engine room and extinguished the boiler fires.

The Clallam was dead in the water, and the wind and current pushed her east, away from Victoria. The crew manned hand-pumps trying to keep her afloat.

At 3:30 p.m., Roberts made two fateful decisions. First, he ordered the crew to launch the three lee side lifeboats. Second, he initiated the Birkenhead Drill, an old code of conduct where the lives of the women and children were to be saved first during a life-threatening situation. It was typically used when abandoning ship.

Lifeboat No. 1 held 12 women and children and a crew of six. Waves capsized the lifeboat and slammed it against the Clallam. Everyone was dumped overboard and drowned.

Lifeboat No. 2 held 10 women and children and a crew of six. It cleared the Clallam, but waves capsized it about 50 feet out. All were lost.

Lifeboat No. 3 was upended by tangled ropes during launch, and all aboard fell into the water and drowned.

Word finally reached authorities, who sent other ships and tugs to rescue the Clallam and its passengers. The steam tug Richard Holyoke found the Clallam halfway between Smith and San Juan islands around 10:30 p.m. They attempted to tow the Clallam to Port Townsend. At 1 a.m. the Clallam listed and began to sink. The towline was cut so the tug wouldn’t be taken down with the Clallam.

The Clallam sunk around 1:15 a.m. about 8 miles from Port Townsend. The remaining crew and passengers were washed into the water. The tug lowered its lifeboats to rescue the survivors. In total, 14 passengers — all men — and 22 crewmen were saved. All the women and children passengers perished when the Clallam launched its three lifeboats.

I was particularly struck by the tragedy’s impact to the Sullins and LaPlant families of Friday Harbor. All four children belonged to these two families and were all related.

H. William LaPlant survived but watched in horror as his wife, Carrie, and daughter, Verna, perished beside the ship. The LaPlants were a young couple, and when his wife and child were washed into the sea, other passengers had to restrain him from diving overboard.

Dellie C. LaPlant Sullins and her children — Leonard, Lewis and Violet — also perished. Her husband, Thomas Sullins, also had to be restrained from diving overboard after his family.

For two weeks, bodies were found along the south shores of Vancouver, San Juan and Whidbey islands. The record states that 56 people lost their lives, but there were probably more than that. Several children who were younger than the fare-paying age were never accounted for.

As expected, several regulatory changes were made to better protect passengers and crew.

A coroner’s jury in Victoria found Roberts guilty of manslaughter, though no formal charges were made. The jury cited the chief engineer for negligence and found the Clallam to be unseaworthy.

This sinking of the Clallam was one of the worst maritime disasters in our history. The sea is an unforgiving master.

________

John McNutt is a descendant of Clallam County pioneers and treasurer of the North Olympic History Center Board of Directors. He can be reached at woodrowsilly@gmail.com.

John’s Clallam history column appears the first Sunday of every month.