FOR US IN Clallam County, the whitecaps in the Straits of Juan de Fuca or the Pacific Ocean remind us of the beauty that comes with living here. But whitecaps and whitecapping also is an ignoble part of U.S. history.

Whitecapping started around 1837 in Indiana. Men began forming secret societies to deliver justice independent of the state.

In general, they aimed their efforts at those who went against community values. They targeted things such as alcoholics, neglectful or abusive husbands, excessive laziness, unwed mothers, horse thieves, murderers and attempted murderers.

At the start, White Cap groups saw themselves as enforcers of morality. It was vigilante justice.

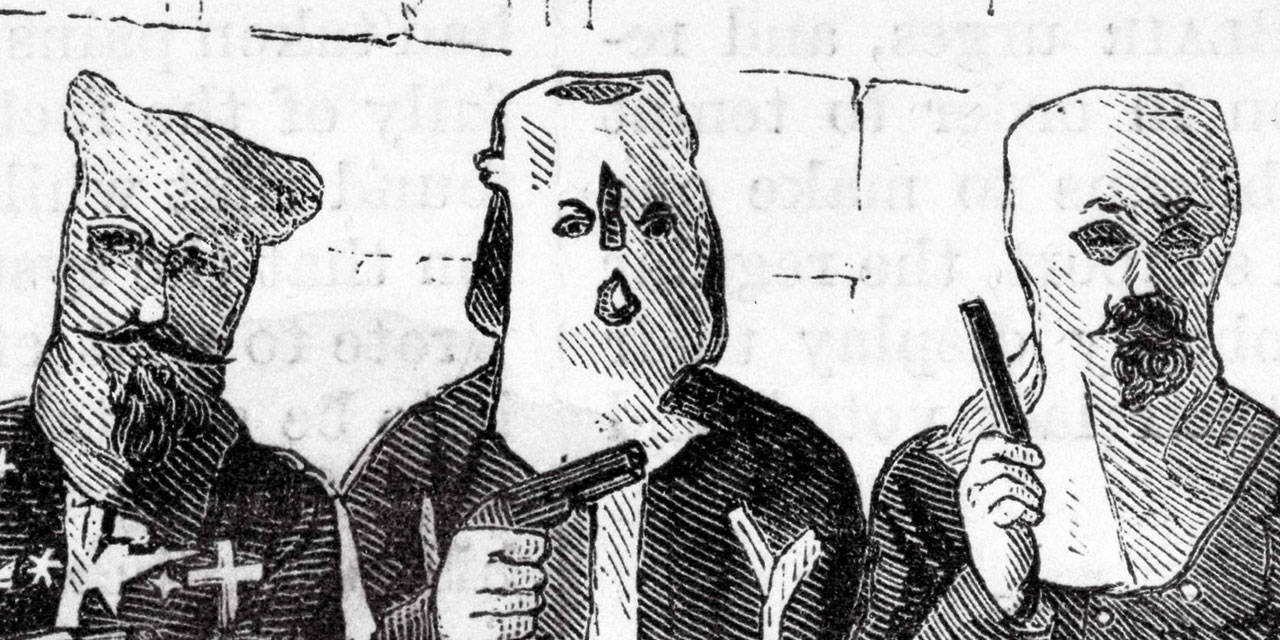

The name is derived simply. To maintain their anonymity, the members of the group would cover their faces with white flour sacks turned inside-out with two eye holes cut out.

Their tactics included whipping, drowning, shooting into homes, arson and lynching. They may start with threats of violence before moving to violence.

We can easily think of White Caps as being prevalent in the Midwest and Southeast United States.

But, in August 1896, Whitecapping came to Clallam County.

This incident was not racially motivated. This was old-fashioned friction amongst neighbors. Western Clallam County was still wild and untamed.

The people involved were all neighbors in the Sol Duc Valley. Friction began over differing opinions in regard to schools, roads and other local matters. It lasted for some time.

Points of view finally crystallized into two distinct factions. Of course, that is nothing new to us today.

The two factions were named the “Garland-Sawyer” group and the “Christopher-Doolittle” group. Both sides felt they were on the right side of the issues, but gossip and slander ensued.

The differences turned to hatred when it came to certain land claims. To give some context, a homestead required a simple three-step process. First, a head of household would file an application. Second, they had to live on the designated land, build a home, make improvements and farm it for a minimum of five years. Third, after five years, they could file for a deed to the land.

Finally, after years of hard work, the time arrived for homesteaders to make proof of residence and secure the title to their claims.

When some of the homesteaders filed for a deed, M.D. Doolittle and D.A. Christopher filed protests. They maintained that some, which included E.E. Hopkins and I.W. Garland, had failed to meet the requirements because they spent too much time away from their farms. Doolittle and Christopher said that Hopkins did not make the required improvements to his claim until after he had filed for title.

Exactly how much time was spent away from their farms is unknown. It is clear that some of the homesteaders spent time in Port Angeles and Forks in other employment to earn money. Regardless, these protests were the last straw for some.

On Sunday, Aug. 23, 1896, Doolittle went to the Collins post office to get his mail. Collins was a post office near Beaver. It was established in 1892 and continued until 1898. Asa Gilbert Collins was its postmaster, hence the name.

Doolittle was on horseback. On his way home, he gave a neighbor’s young daughter a ride toward home. Along the trail, Doolittle was met by 11 armed Whitecaps. All guns were pointed at Doolittle, and he was ordered to stop. He complied. The little girl was sent home. I’m sure she was quite frightened by the sight of armed men wearing white hoods.

Doolittle was taken from his horse and stripped of his coat and shirt. His clothes were used as a blindfold. After his hands were tied, he was taken into the woods and held for about four hours. The reputation of Whitecaps, in general, was common knowledge. So, Doolittle had plenty of reason for being apprehensive and fearful for his safety. Finally, a coat of hot pitch was applied to Doolittle’s upper body, and then feathers were applied to the pitch.

The Whitecaps took Doolittle to the post office. They called out Postmaster Collins to witness them placing Doolittle on a rail as an object lesson. They warned Doolittle not to meddle in other men’s land claims and to leave the Sol Duc valley. They also threatened Doolittle with death if he reported these events.

Fueled by anger more than fear, Doolittle went home to fetch his rifle. His wife was frightened so he stayed until later in the afternoon. It also gave him time to clean off the pitch and feathers.

The Whitecaps were next seen in Sappho looking for Christopher. Local people determined that the Whitecaps were setting up an ambush on the road between Forks and Beaver. The Whitecaps finally gave up when Christopher never showed.

Doolittle knew the Whitecaps’ intentions were the same for Christopher as they were for him. He and a friend, M. Bigler, armed themselves and set out on foot to warn Christopher of the threat. Along the path, they came face-to-face with the Whitecaps.

By that, time it was dark and getting hard to see.

Doolittle and Bigler claimed the Whitecaps fired first on them. Regardless of who fired the first shot, a volley of gunfire erupted between the two groups.

Doolittle and Bigler ran to the Sol Duc River, where they hid until morning. The next morning, Doolittle and Bigler went to Forks to tell of their experiences and solicit help, warning Christopher of the danger he was in. Eight men quickly organized and rode to Beaver intending to warn Christopher. Christopher had already received word and was safe.

The only apparent injury was to Darwin Hopkins, one of the Whitecaps. Darwin’s injury was near his eye. It was serious enough to require medical treatment. Four friends carried Darwin to Port Angeles for treatment.

By Tuesday, Christopher, Bigler and Doolittle were also in Port Angeles. Christopher was attending the Republican county convention as a delegate. The two groups continued to be antagonistic toward each other, but it never went beyond words. Their dispute didn’t go away, but at least it never reached the same level of belligerence exhibited in the Sol Duc valley.

No one would tell whether the shooting was intended to scare or kill. The reputation earned by Whitecaps in the United States would cause fear and trepidation to any sensible person.

We don’t have Whitecaps today. Yet, I have observed that we find new ways to do the same thing. Now people hide behind masks, hoods, bandanas and social media. History repeats itself. I can only wonder, “Have we changed that much?”

________

John McNutt is a descendant of Clallam County pioneers and treasurer of the North Olympic History Center Board of Directors. He can be reached at woodrowsilly@gmail.com.

John’s Clallam history column appears the first Sunday of every month..