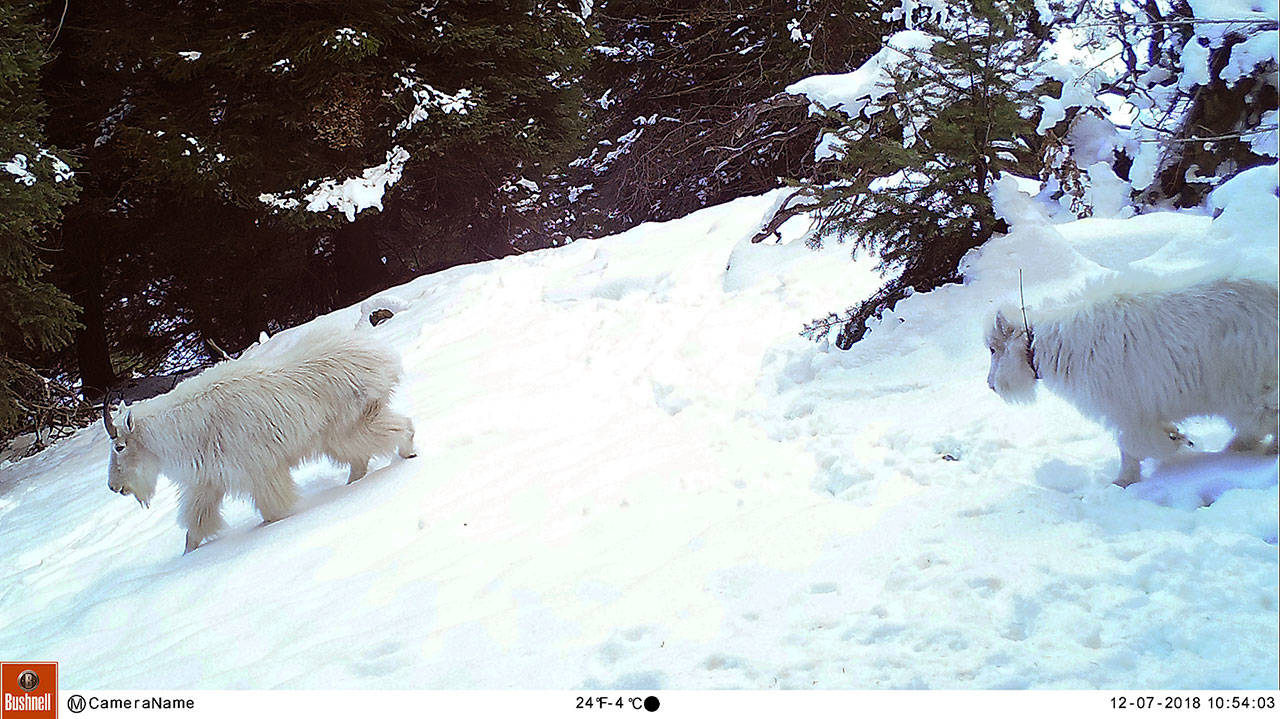

A science experiment conducted in real time, the translocation of mountain goats from the Olympic Mountains to the Cascade Range has provided federal and state biologists with a number of initial takeaways on whether the agile ungulates are gaining a proper foothold in their new habitats or simply scrambling for purchase.

Biologists say the survival rate of resident Cascade mountain goats is 80-90 percent each year, and through the first three translocation operations, the survival rate of translocated animals is 79 percent, with at least 173 mountain goats known to be alive, 46 others dead and the status of 24 additional goats unknown as of a November 2019 progress report.

First-year survival for resident mountain goat kids is typically about 50 percent, and despite expecting to see higher mortality rate due to the stress of translocation and adapting to new home ranges, as many as 22 of 34 kids released in 2018-19 were potentially alive, more than 60 percent, biologists said.

Mountain goat capture by helicopter and relocation from Olympic National Park and Olympic National Forest lands to native habitat on U.S. Forest Service land in the Cascades began in late summer 2018 with the hope of rounding up about half of the park’s estimated population of 725.

Mountain goats are native to the Cascades, although they were absent or rare in some areas. The goats are not native to the Olympics, having been introduced in the 1920s as game animals.

Officials said the Olympics goats were hurting vegetation, and some had become aggressive toward people.

A total of 381 mountain goats were captured and 325 animals released in North Cascades national forests after the fourth and final two-week helicopter capture operation in Olympic National Park and the Olympic National Forest wrapped up earlier this month.

Zoos provided permanent homes to 16 mountain goat kids, while 22 died during capture.

Six animals were euthanized because they were unfit for translocation and four others died in transit.

An additional eight mountain goats that could not be captured safely were lethally removed.

Remaining mountain goats in Olympic National Park will be culled in lethal removal operations conducted between Sept. 9 and Oct. 17 by 21 teams of three to six outdoors enthusiasts evaluated by National Park Service and state Department of Fish and Wildlife staff.

Mountain goats that remain will be lethally removed in aerial operations in 2021 and, if necessary, 2022, Olympic National Park spokesperson Penny Wagner said.

A progress report authored Nov. 5, 2019, by Olympic National Park Wildlife Branch Chief Patti Happe and state Department of Fish and Wildlife biologists Rich Harris and Bryan Murphie provided the most recent in-depth information on mountain goat translocation operations and the acclimation of relocated animals.

The first 50 days following translocation were especially hazardous with an estimated 10 percent of translocated mountain goats perishing.

“Survival improved slightly for the next 50 days, and approached what one would generally expect from a resident population following that,” the report stated.

Survival in high alpine regions is a struggle for most species, mountain goats included.

Causes of high mortality include avalanches, falls, predation, parasites and poor winter conditions which can cause stress.

“We would expect survival rates of resident mountain goats to be in the range of 80 to 90 percent and for those survival rates to be fairly consistent from year to year,” Fish and Wildlife Ungulate Section Manager Brock Hoenes said.

“Relative to translocated mountain goats, it’s difficult to define an expected survival rate beyond stating that we expect it to be lower.

“The reason for that is because survival rates of mountain goats among all the relocation efforts that have occurred over the years across North America have varied widely with a wide array of factors, including the number of goats released, habitat, goat condition, capture method, handling procedures, etc., contributing to the success or failure of those translocation efforts,” the report continued.

“That being said, we do expect the survival of translocated mountain goats to be similar to resident goats following the first year of translocation, and that is what we have observed on this project.”

Mountain goat kid survival was better than biologists expected.

“As documented in the Federal Environmental Impact Statement, we expected survival of translocated kids to be poor,” the report said.

A total of 34 kids were released in 2018 and 2019, many with breakaway GPS or VHF tracking collars.

Four of 11 kids released in 2018 were alive as of March 2019, while five mortalities were documented out of 23 released in 2019.

“During the combined July and August 2019 translocations, we released 23 kids … as of this writing, we have documented five mortalities among these kids, and five of the six kids wearing GPS collars and thus providing real-time data on survival remain alive.

“Given that over-winter survival of resident kids is typically around 50 percent, that we expected it to be lower than that due to the stress of translocation and adapting to new home ranges, and that — despite our efforts — nannies did not stay with their kids post-release, we are pleasantly surprised to find kid survival this high.”

Despite efforts to keep nanny/kid pairs together during translocation, 13 observed nanny goat/kid pairs had separated, with most more than 5 kilometers apart.

“They go to open these boxes, and some are just gone, some go the other way, others take a while to get themselves up and moving,” said William Moore, Department of Fish and Wildlife biologist.

“We pull the kid out of their box, have a biologist standing next to a nanny’s box with her kid, and whatever direction they come out, they line that kid out so it’s right on the tail of the nanny. That’s worked pretty well.”

Biologists also use oxytocin, a bonding hormone, to keep nannies interested in mothering their offspring.

Reproduction has been documented in small sample sizes. That was expected as only 14 of 98 animals released in 2018 were adult males, and all released animals had little time to adapt to their new surroundings.

Western Washington University students observed eight of 18 candidate nannies last summer, three of which had given birth.

Muckleshoot tribal biologists additionally confirmed kids with three of six nannies they were able to visually identify in August 2019.

And biologists have hope for the future of the translocated animals.

“The augmentation of the mountain goat population is extremely helpful,” Moore said. “From I-90 to [state] Highway 20, the habitat has been filled in by these animals. It’s a pretty amazing data set that we are collecting. There are hundreds of animals involved, and most have GPS collars, so it’s a pretty sizeable project.

“It’s a really big win-win. We’ve been able to get them into the right habitat in the Cascades and out of the Olympics, and from what has been observed so far, it’s been a real success story for both areas.”

________

Sports reporter Michael Carman can be contacted at 360-406-0674 or at mcarman@peninsuladailynews.com.