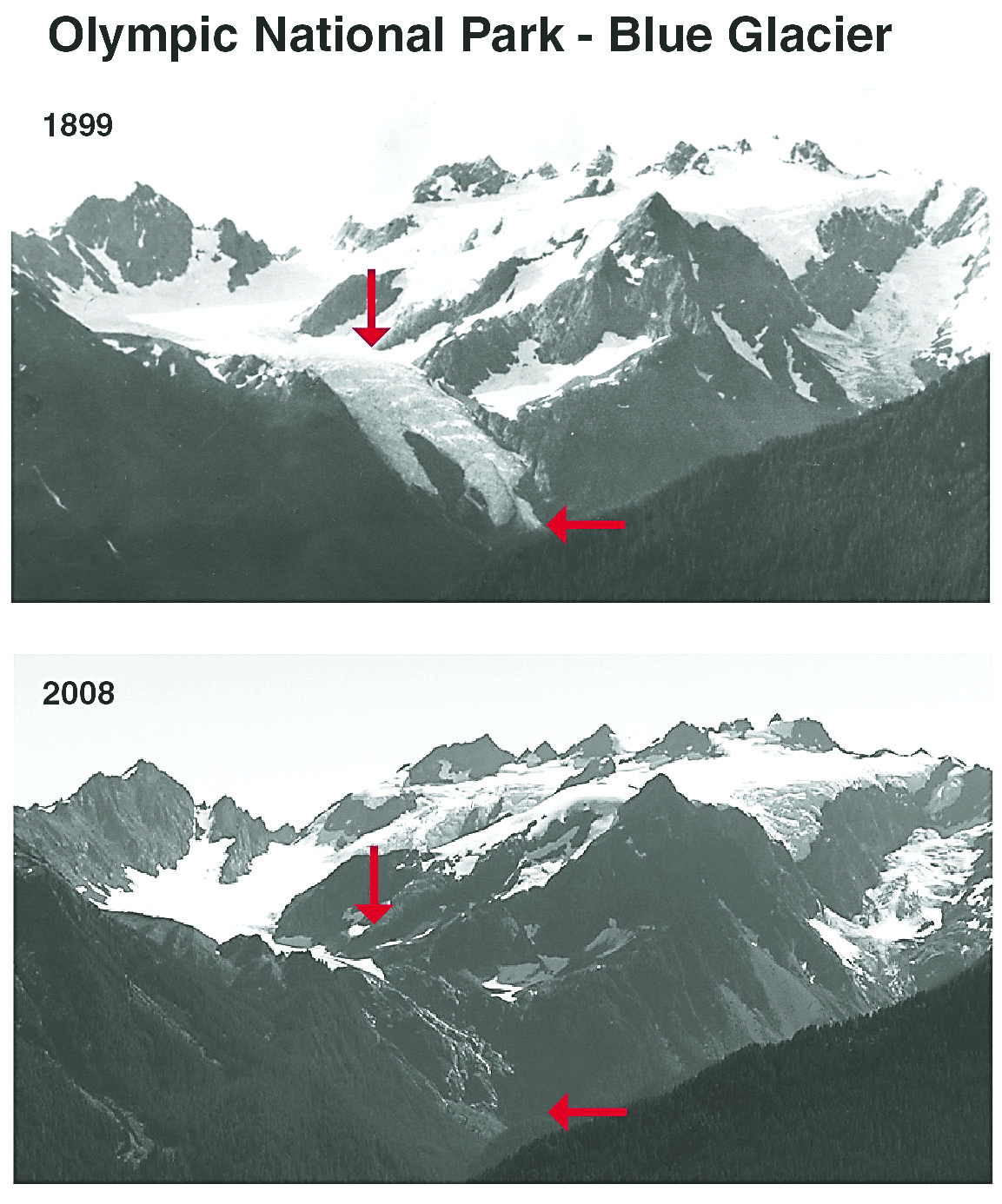

PORT ANGELES — The pictures tell the story:

Glaciers are receding in the Olympic Mountains and around the world, a team of University of Washington researchers told an overflow audience at the Olympic National Park Visitor Center.

Blue Glacier on Mount Olympus, the largest and most studied glacier in the national park, is being monitored for clues it may reveal about long-term changes in snowfall and temperature, said Michelle Koutnik, a UW research professor.

“The new observations that we’re getting from the satellite imagery opens up a whole new level of understanding and ability to monitor that change and make projections,” she said.

A crowd of about 100 packed into the small auditorium at the visitor center to hear Koutnik and fellow UW research professor Howard Conway discuss the past, present and future of Blue Glacier.

Blue Glacier on the north face of 7,980-foot Mount Olympus has been studied since 1957, providing a record longer than most glaciers in North America.

From 1987 to 2010, the sweeping, heavily crevassed glacier lost about 180 feet of thickness on its lower sections and about 33 feet of thickness on its upper accumulation zone, said Bill Baccus, Olympic National Park physical scientist.

An entire section of the lower Blue Glacier that existed in an 1899 photograph was long gone by 2008.

“There’s insight to gain from having historical photographs, even if you don’t have quantitative information from them all the time,” Koutnik said.

“In the more recent era, we know it’s lost about 15 percent in volume. There’s some uncertainty in that, but it’s on an approximate scale.”

Basin-wide, the surface area of all glaciers in the Olympic Mountains shrunk 34 percent from 1980 to 2010, Baccus said.

There were 266 glaciers in the park in 1980 compared with 184 now, Baccus said.

“Most of them are small and four of them are large, like we know Blue Glacier to be,” Koutnik said.

The National Park Service has a website dedicated to glaciers and climate change in Olympic National Park.

Click on www.tinyurl.com/PDN-ONPglaciers.

The site features interactive tools and before-and-after photographs showing how the Lillian and Anderson glaciers have virtually disappeared.

South-facing glaciers and glaciers at lower elevations are particularly susceptible to melting because of their direct exposure to the sun and relatively warm temperatures.

“Those valley glaciers,” Baccus said, “could very well disappear for the most part in the next 100 years.

“It would kind of pull up into that upper cirque.

“Maybe not in the Blue, but in a lot of our glaciers, it will kind of pull up out of the valley — like what we’ve seen with the Carrie Glacier, for instance, where it’s really no longer down in the valley.”

Conway displayed a series of slides depicting early research on the Blue Glacier.

Scientists dug tunnels to map the bottom of the glacier and buried snow sensors and markers on the surface.

“Now we’re in the satellite era.” Conway said. “We’ll do a lot more in the near future.”

For the past three years, monitoring of the Blue Glacier has been funded with donations thorough Washington’s National Parks Fund, Baccus said.

“That’s really enabled us to pick this back up, kind of where the UW had left off, and tried to incorporate into our long-term monitoring program,” said Baccus, who co-authored a recent study on Olympic Mountain glaciers and their contribution to stream flow.

Long-term glacier monitoring can be used to study climate because glaciers are sensitive to changes in snowfall and temperature, Koutnik said.

“It’s a simple equation of what comes in and what goes out,” Koutnik said.

“And it’s mainly snowfall coming in and melting taking mass off the glacier. There can also be complications with wind drifting and avalanching, and that can go either way.

“And the sum of these, generally, would give you this net balance over one year.”

Conway said 2015 is “shaping up to be a very, very bad year” for the Blue Glacier because of the low snowpack.

As of April 1, snowpack in the Olympics was just 3 percent of normal.

Conway concluded Tuesday’s program by saying the Blue Glacier has been losing mass at an accelerated rate in the past decade.

“And like other glaciers around the world, it’s shrinking,” he said.

The free lecture was the last in Olympic National Park’s Perspectives Winter Speakers Series, which began in November.

________

Reporter Rob Ollikainen can be reached at 360-452-2345, ext. 5072, or at rollikainen@peninsuladailynews.com.