The Associated Press

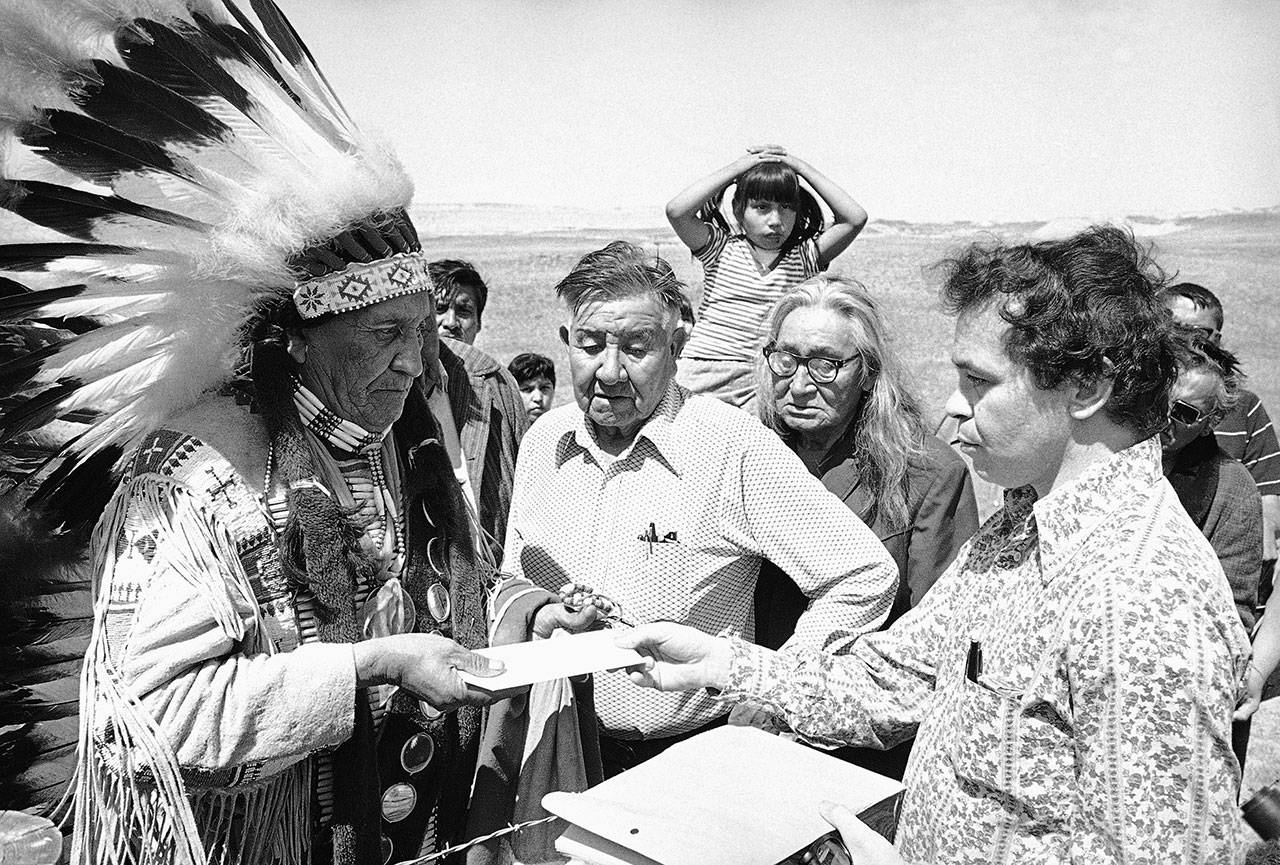

Hank Adams, one of Indian Country’s most prolific thinkers and strategists, has died at age 77.

Adams was called the “most important Indian” by influential Native American rights advocate and author Vine Deloria Jr., because he was involved with nearly every major event in American Indian history from the 1960s forward.

He was perhaps best known for his work to secure treaty rights, particularly during the Northwest “fish wars” of the 1960s and ’70s.

Henry “Hank” Adams, Assiniboine-Sioux, died Monday at St. Peter’s Hospital in Olympia, according to the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission.

“Hank’s a genius. He knows things we don’t know. He sees things we don’t see,” attorney Susan Hvalsoe Komori said when Adams was awarded the 2006 American Indian Visionary Award by Indian Country Today.

“Adams was always the guy under the radar, working on all kinds of things,” said the late Billy Frank Jr., Nisqually and chairman of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission.

Adams was born in Wolf Point, Montana. Toward the end of World War II, his family moved to Washington state, where he attended Moclips-Aloha High School near the Quinault Nation. He played football and basketball and served as student body president and editor of the school newspaper and yearbook.

In 1963, Adams joined the National Indian Youth Council, where he began to focus on treaty rights just as the fish wars were beginning and Northwest tribes were calling on the federal government to recognize their treaty-protected fishing rights.

Adams had so many personal connections with people from that era, such as Mel Thom, Clyde Warrior and Willie Hensley. It was while Adams was working with the youth council that he first met Marlon Brando. The actor would be prominent later in the Frank’s Landing protests.

Also through the youth council, Adams began working at Frank’s Landing, on Washington’s Nisqually River, with Billy Frank and others who were striving to advance the treaty right to fish for salmon.

“That turned into a civil rights agenda,” Adams said in an interview. “It had been brutal from 1962 onward, and there were just a few fishermen down there, fighting with their families for their rights.”

To make a point, Adams refused induction into the military because the U.S. was failing to live up to its treaty obligations. (He eventually served for two years in the U.S. Army.)

As Washington state’s fish wars heated up in the 1960s, Adam was often working with Frank and other Northwest leaders on a strategy of civil disobedience through “fish-ins.”

Frank told a story about a 1968 fishing protest in Olympia “where all the police are.” But not everyone was supposed to be arrested. Frank said it was the job of Adams, the “visionary,” to protect them all. But when the arrests were made, “here comes our visionary.”

“I said, ‘What are you doing here? You’re supposed to get us out. You’re the strategist, thinking way out into the future,’ ” Frank said.

It was from those many trips to jail that eventually treaty-protected fishing rights were upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court. The Boldt decision affirmed the tribal right to fish in the usual and accustomed places in common with other citizens.

Adams’ role in the trial, which took place in Tacoma, Washington, was unprecedented. He was a lay-lawyer representing tribal fishing people and the last person to speak at trial. The judge considered Adams the most informed person to explain both the treaty and the people.

As the court case made its way through the process, Adams and Billy Frank found a way to meet with Judge George Boldt in chambers.

“We don’t want to talk to you about the case,” Adams recalled at the 40th anniversary dinner of the Boldt decision. Instead, the pair met with the judge to tell them that Montana Sen. Lee Metcalf was an admirer of the judge, who was also from Montana. They swapped Montana stories. And, the joke was the case could be resolved if it was just Montanans in the room.

The Supreme Court affirmed treaty rights and the Boldt decision in a series of cases in 1975.

Shortly before the 1972 election, a caravan of American Indians travelled from points across the country to Washington to protest broken treaties. After failed negotiations for housing, the protest ended up at the Bureau of Indian Affairs. And when the bureaucrats left for the day, the protestors remained.

Adams was also instrumental in resolving the 1972 takeover of the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Richard Nixon’s special assistant, Leonard Garment, said Adams’ role was essential. He said the story could have been tragic, with some in the administration calling for a military assault on the building.

Adams was both a public foil and a behind-the-scenes negotiator. The Trail of Broken Treaties submitted a plank of 20 proposals. Adams called the Nixon administration’s response “almost totally devoid of positive comment.”

But privately Adams and Garment worked on a resolution. Adams’ reward for being an intermediary? He was arrested in 1973 and his home searched for “government documents.”

“Plus they took my typewriter, which I’d had since 1968 during our encampment on the Nisqually River,” Adams said.

A federal grand jury refused to indict Adams (along with journalists who had been reporting on the incident), and eventually Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus ordered the material returned. He “directed the FBI to return everything that they’d taken from me and particularly my typewriter,” Adams said with a laugh.

Adams played a similar role during the standoff at 1973 Wounded Knee. He said a government helicopter flew him to White Clay, Nebraska, where he was to meet with the Justice Department’s Community Relations Service.

After that meeting, Adams was set to meet in Denver with Marlon Brando. The Justice Department was supposed to drive Adams back to the airport, but “they ran out of gas within sight of the airport.” Adams laughed. “The federal government doesn’t run out of gas. They didn’t want me to meet with Marlon Brando” and stir up public support for the occupation.

Using social media, Adams was meticulous over the years in his documentation of family histories, often used to help people grieve over the loss of family, or to call out people who lied and claimed Indigenous ancestry. He continued to monitor and press for treaty rights. And for Leonard Peltier’s release from prison.

Adams’ family said a funeral is not possible at this time, but it will co-ordinate a memorial in the near future.

________

Information for this story is from Indian Country Today at https://indiancountrytoday.com/