By Dave Itzkoff New York Times News Service

It was a typical week for late-night television earlier this month:

■ On NBC’s “Tonight” show, the host Jimmy Fallon played a catchphrase guessing game with the “Modern Family” star Sofia Vergara, and re-enacted the music video for the 1990 rock ballad “More Than Words.”

■ On ABC’s “Jimmy Kimmel Live,” Kimmel watched a hidden camera to see how Los Angeles pedestrians would react to a burrito dangled above Hollywood Boulevard.

■ And on CBS’s “Late Late Show,” James Corden asked pizzeria customers to choose between the pies they had ordered and the contents of a mystery box.

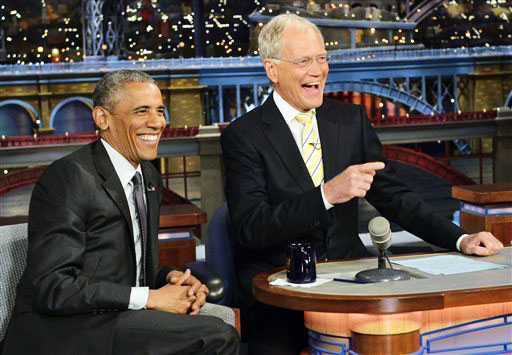

■ On CBS’s “Late Show,” David Letterman was interviewing President Barack Obama — a ruminative, sometimes funny, casual conversation between two men who seemed almost like peers, joking about how they might share a game of dominoes after they retire.

Letterman, of course, will make that transition first: He is ending his 22-year run on “Late Show” (and a 33-year late-night career) on May 20.

When he walks out of New York’s famously chilly Ed Sullivan Theater for the last time, he will be leaving a late-night landscape that, while brimming with potential and still attracting millions of viewers, is also scrambling to redefine itself in a world where late-night TV shows are increasingly not being watched at night, not for more than a few minutes and not on a TV.

If Letterman represented an era when a late-night show was a comprehensive end-of-day viewing experience, meant to be watched in a post-twilight setting for an hour (or until you fell asleep), the coming age is fragmented by technology, designed for online virality, unstructured and unmoored from time slots.

“People are just plucking your greatest hits, without having to sit through the rest of the show,” Kimmel, 47, the ABC host, said.

“There’s more focus on singles than on albums.”

Many of the classic trappings of late-night shows are still visible: opening monologues, house bands and desk-side celebrity chitchats.

What is going away is the expectation viewers will watch these programs in close to their entirety, or even sequentially.

And future shows will abandon the familiar, rhythmic tempo of late-night altogether.

Next year, Chelsea Handler, former host of the E! series “Chelsea Lately,” plans to introduce a Netflix series that can be watched at any time of day and whose contents could vary widely from episode to episode.

In the meantime, the people creating late-night television are experiencing varying degrees of head-scratching and hand-wringing and periods of Internet sniping as they try to determine how to distinguish their programs.

Seth Meyers, who hosts NBC’s “Late Night,” observed that nearly every comedy component that was once unique to the field has been co-opted elsewhere, but each performer can still find a signature element to stand out in the crowd.

Asked if topical competitors like “The Daily Show” on the Comedy Central channel had taken away some of his opening-monologue turf, Meyers, 41, replied, “Certainly.”

He added: “Someone has the market cornered on everything, but no one has a monopoly on everything.

“I’d like to have a show that is good at a lot of different things, as opposed to just one thing.”

In a positive development for these shows, the Internet has allowed them to reach larger audiences while their broadcast ratings remain healthy.

Fallon, 40, the 11:35 p.m. champion, has nearly 4 million nightly viewers, while Kimmel and Letterman get about 2.7 million each.

(These numbers are down over all from earlier, less fragmented eras — Jay Leno’s “Tonight” show drew about 6 million viewers and Mr. Letterman’s “Late Show” about 4 million when they went head-to-head in the 2000s.)

A successful online video from one of those shows, however, can be even more powerful.

A reunion of the “Saved by the Bell” cast or a woman appearing to set herself aflame while attempting to twerk can receive tens of millions of views.

Still, there is concern that pursuing online virality for its own sake will backfire.

“You cannot be chasing that, because it’s futile,” said Corden, 36, the British actor who took over “Late Late Show” in March.

“If you just want to have a great viral clip,” he added, “I’ll strip naked and run down Sunset Boulevard. That will get loads of views.”

Others have criticized the use of these offbeat segments for creating an overly clubby sensibility.

In April, Andres du Bouchet, a writer for TBS’s “Conan,” criticized other programs for an overreliance on gimmickry that he called “Prom King Comedy.”

“No celebrities, no parodies, no pranks, no mash-ups or hashtag wars,” du Bouchet wrote in a series of Twitter posts that were later deleted.

“You’ve let the popular kids appropriate the very art form that helped you deal,” he wrote. “None of the funniest stuff ever involved celebrity cameos.”

Du Bouchet, who appeared to be attacking rival hosts like Fallon, was reprimanded by his own boss.

Conan O’Brien, the former “Late Night” and “Tonight” show host, wrote on Twitter that one of his writers should “focus on making my show funnier instead of tweeting stupid things about the state of late-night comedy.”

Through their press representatives, Fallon, O’Brien and their staffs declined to comment for this article.

Stephen Colbert, 50, who played an acerbic political commentator on “The Colbert Report” on Comedy Central, will set aside his character when he takes over at “Late Show” in September.

Prospective writers for his “Late Show” have been told the host still enjoys “active and silly comedy,” according to a set of submission guidelines these writers were provided, and have been asked to pitch jokes based on news stories as well as comedy bits Colbert can perform with guests.

Letterman, whose “Late Night” program on NBC provided a cutting-edge companion to Johnny Carson’s “Tonight” show in the 1980s, was welcoming of this latest wave of change.

Going back to the creation of the “Tonight” show in 1954, Letterman said:

“If you take a look at early Steve Allen shows, I’ll bet you could find versions of what is now being done — maybe not as slick, certainly not in color.”

Letterman said the seeds of change “were sown decades ago, and good for these guys that they found something else to do.”

Inevitably, for every late-night era, what once seemed daring and unfamiliar will someday become the tradition for the next generation to push against.

“Over 20 years ago, we said goodbye to Carson,” said Nell Scovell, a former writer for Letterman’s “Late Night” program.

“This month, we’ll say goodbye to Letterman,” she added.

“And 20 years from now, we’ll all lip-sync goodbye to Jimmy Fallon.”

________

Dave Itzkoff writes on cultural issues for The New York Times, where this essay first appeared.