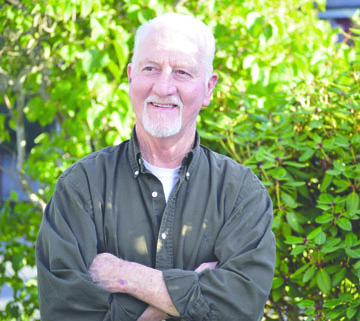

Brian Doig remembers waking up nine days after the event.

His first thought: “Is this a dream? Or is this real?”

For Doig, a singer who has undergone a double lung transplant, there have been hopes and dreams realized — and the dark moments.

As a young man in Los Angeles and Orange County, Calif., he sang with the acclaimed William Hall Chorale and performed in venues such as the Hollywood Bowl.

And for this musician, lifting his voice has always equaled joy. He’s spread that joy for a lot of years, said Dewey Ehling, conductor of the Peninsula Singers, one of the ensembles Doig has sung with.

The Peninsula Singers will pay musical tribute to Doig today with a concert: an afternoon of songs ranging from “Sure on This Shining Night” to “Beautiful Dreamer,” offered by Doig’s friends and fellow musicians.

Doig has not used his instrument for a year and a half now. The last show he sang in was “Plaid Tidings,” the hit musical at the Dungeness Schoolhouse in 2011, back before his lungs began to fail.

Doig was stricken with interstitial lung disease, a progressive ailment that scars the lung tissue, leaving the patient bereft of oxygen. The causes aren’t entirely clear, according to MayoClinic.com, but the illness has been connected to long-term exposure to hazardous materials such as asbestos.

Doig, in addition to his singing, worked for the Clallam County Road Department for 27 years; he retired eight years ago.

In a conversation about his health, however, he speaks of the future, and of his gratitude for what he calls a second chance at living.

His daughter Lorrie Kuss, also a singer, remembers when he took a turn for the worse. On a family camp-out in 2011, Doig had begun using an oxygen tank, and Kuss could see that he was struggling.

“I realized he was sicker than he was letting on. I said, ‘I totally get that you want to protect us. But I want to know. I don’t want any surprises.’”

For the next six months Doig’s health slid downhill, till his need for supplemental oxygen was constant.

And he went from being muscular — “buff,” as Kuss puts it — to having to stop and rest after walking a few steps.

Ehling, too, remembers what the disease did. Doig is a pillar of the musical community, part of productions staged by Olympic Theatre Arts, the Sequim Community Christmas Chorus, Readers Theatre Plus, PALOA and the Peninsula Singers.

“He is a wonderful baritone,” Ehling said. “But he has always sung tenor for us,” in the Peninsula Singers, “because it was so needed.

“Whether it’s a solo or the least part of an ensemble, his spirit is in it, all the way”.

And when it comes to setting up risers and folding chairs, “he’s the first one to volunteer.”

As Doig’s lungs grew sicker, it wasn’t his voice that changed so much, Ehling said. It was his oxygen supply.

“He didn’t have any air. It was hard to phrase; he had to gasp.”

The oxygen tank helped, but it dried the singer’s throat. By the winter of 2012, Doig was too ill to do much of anything. His doctors urged him to take the battery of tests required for placement on the lung-transplant list.

His and his family’s hopes were raised on the afternoon of Feb. 20 when Doig was given the news that yes, he was now on the list.

When he and his wife of 28 years, Anne, retired that night, Doig did something unusual: He brought the telephone into the bedroom.

At 2:30 a.m., it rang.

The call, from the University of Washington Medical Center, summoned him to the hospital for surgery.

The Doigs climbed into the car and drove to Kingston, where they waited 45 minutes for the ferry to Edmonds.

Brian Doig did the driving that night, of course. He’s not the type to sit in the passenger seat.

Yet he and Anne knew this could turn out to be a “dry run,” since transplant teams sometimes find that the donated organs are not strong enough. The would-be recipient has to turn around and go home.

But when Doig arrived at the hospital, he had a feeling.

He remembers thinking: “This is a go.”

Surgery began at 10:30 a.m. Five and a half hours hence, Doig’s two diseased lungs were replaced by new ones.

For days, he lay in the hospital, heavily sedated.

“I remember visualizing my wife,” at one point, but for the most part, “I was too tired to open my eyes.”

Doig was required to stay in the Seattle area for three months following the transplant. Several family members, including his two daughters — Kuss, who lives in Port Angeles, and Tricia Stratton of Sequim — cared for him until he was ready to return home in May.

Ehling remembers seeing his friend soon after that.

Doig drove from his home in Sequim to Ehling’s in Port Angeles with precious cargo: tomato plants, raised by Doig’s son-in-law Mike Stratton.

He had no business hauling these plants, but he did so, placing them in a sunny spot on the front porch for Ehling.

Doig and Ehling, who is in his mid-80s, knew they were kindred spirits back in 1986, when Ehling moved to Port Angeles. Doig had just sung in the Port Angeles Light Opera Association musical “Little Mary Sunshine,” and it didn’t take long for the two men to start working together in the Peninsula Singers.

Doig has done his tomato delivery every spring for years now.

This fall, “those tomatoes are flourishing,” said Ehling.

Next month, Doig will be 70. He expresses deep gratitude for his family: his daughters and his sons Jason and Brian; 15 grandchildren, one great-grandchild and another on the way. And after decades in Sequim, he still loves this place.

Recovery from a double lung transplant is, he says, “an amazing journey.”

He has an exercise and stretching program that is not easy on the scar that crosses his torso. He has just finished the pulmonary rehabilitation program, and he’s on antibiotics for a lung infection. Some days, everything tastes like metal.

The passing weeks have brought peaks and valleys; one of the ups was when Doig learned that a local woman with lung disease received a transplant after two and a half years on the list.

“I hardly know this woman,” he said. But “I was jumping up and down. I knew exactly where she was.”

Doig credits his surgeon, Dr. Michael Mulligan, for his extreme skill, and adds that the care he received at UW Medical Center was “phenomenal.” He returns to Seattle for follow-up appointments every few weeks, and at his first one in June, one doctor said, “Before you know it, you’ll be able to drive.”

Doig’s sheepish look gave him away: He had driven himself that day from Sequim to the UW.

His assignment now is to gain pounds, to reach his pre-transplant weight by the first anniversary of his operation on Feb. 21, 2014. Which, he says with a straight face, means “I’ll have to eat like hell through the holidays.”

What would make Doig feel like himself again, though, has to do with his art.

He hopes to sing again.

“I sure do miss it.

“When you sing . . . you have to be happy. And seeing the audience enjoy it makes it even better.”

And if he could sing any two songs in the world, what would they be?

“The Impossible Dream” has always been a kind of signature song.

The other is “My Way,” Doig added with a smile. “It fits the shoe.”