EDITOR’S NOTE: See accompanying fact box, at lower right.

TODAY WE CELEBRATE one Independence Day, though, with so many versions of America, it’s hard to know how to reconcile them all.

All across the country, we differ, sometimes gently, often sharply, on what rights obtain, what liberty allows, what freedom permits.

That tension is characteristically American.

Even on our best days — and the Fourth of July is one of them — we seem more pluribus than unum, though your neighbor’s idea of who belongs to our pluribus may be radically different from yours.

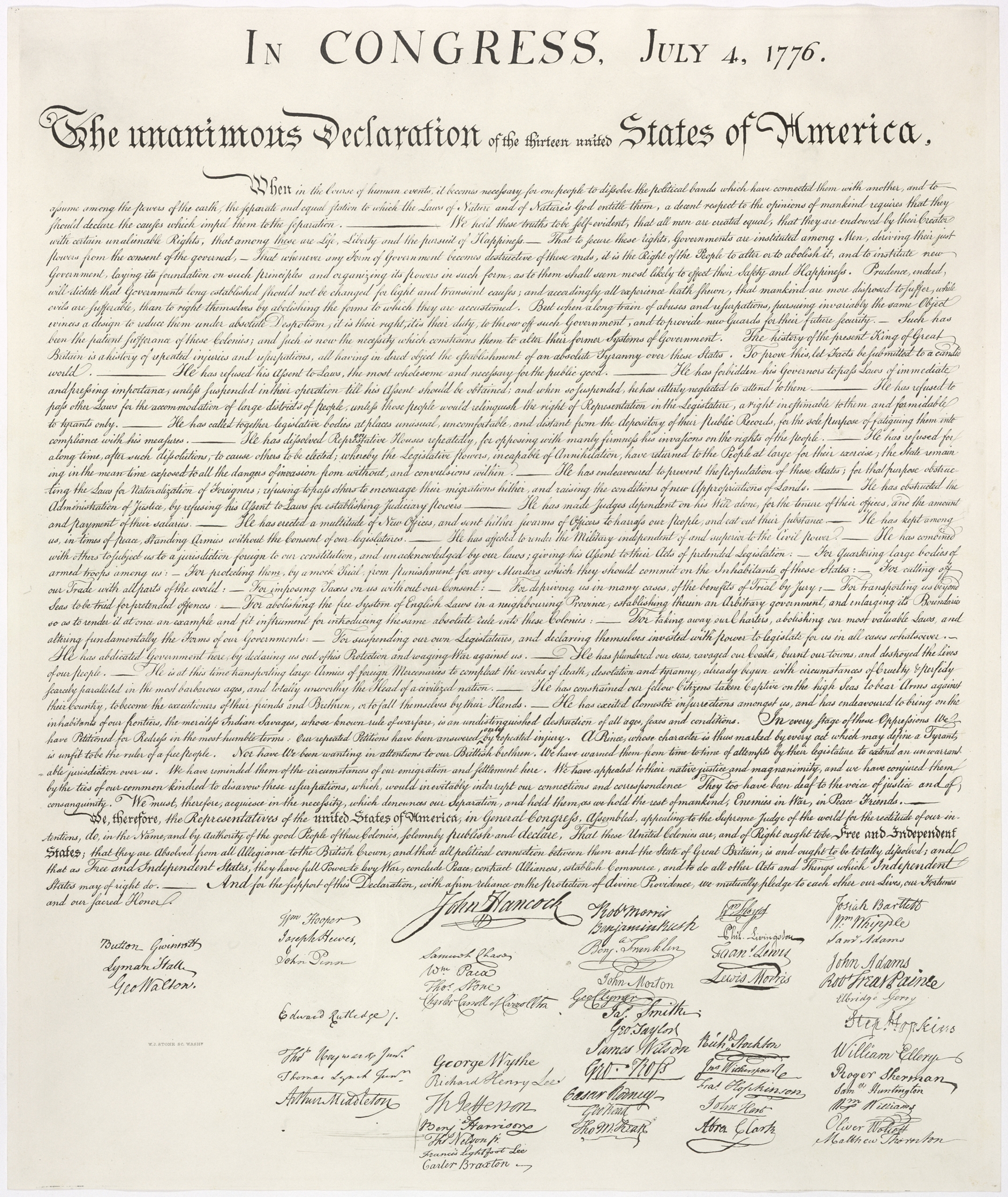

Given the nature of our founding and the documents that created this country, we seem destined to quarrel endlessly about who we are and who we’re supposed to be.

This sounds like a flaw, but, in fact, it’s a peculiarly American virtue.

Our history may read like a narrative, but it’s really a debate, sometimes bloody, usually peaceful, but always unresolved.

We remain divided on nearly all the major elements of our constitution: the role of religion, the balance between federal and state authority, the risks and consequences of unlimited opportunity, the boundary between self-reliance and shared responsibility.

On the Fourth of July in an election year, we find ourselves clamoring for a clear description of something politicians rarely talk about clearly.

What should America look like? Who should we be to each other? There is too often a starkness to the American language of opportunity, as if you deserve what you get if you don’t get what you want, as if we were a loose confederation of individuals instead of a people.

It is fine to sit back and watch the fireworks in the night. But the Fourth of July isn’t a day off from something. It’s a holiday for rethinking who we are.

— Editorial in The New York Times, July 4, 2012