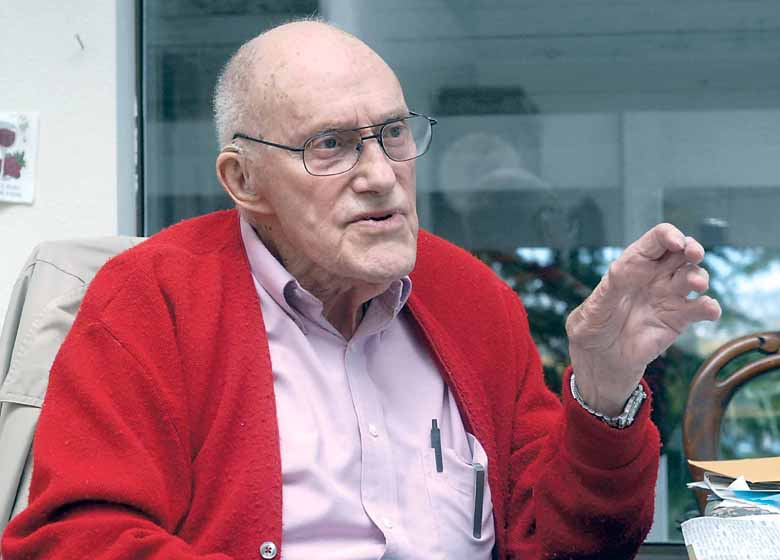

PORT ANGELES — In this city, Duncan Yves McKiernan is best-known for his public art displays, including “Cormorants,” the larger-than-life bronze sculpture of two of the majestic sea birds that has graced City Pier since 1980.

But McKiernan, 89, has another claim to fame.

Seventy years ago Monday, McKiernan was among the U.S. troops that joined Gen. Douglas MacArthur as the general famously made his way through the surf onto the island of Leyte in the Philippines during World War II.

“I shall return,” MacArthur said when he and his troops were driven from the Philippines’ Corregidor Island in March 1942.

MacArthur made good on that promise, wading ashore on Oct. 20, 1944.

Just a few hours later and a few miles south, Marine Pfc. McKiernan also made his way onto the island to play his part in the Battle of Leyte, which was part of the Philippines campaign aimed at liberating the archipelago from Japanese occupation.

Asked if it felt like 70 years have passed since that landing, McKiernan answered with a laugh: “It feels like a hundred.”

McKiernan was attached to the 155 Howitzer Battalion of the 5th Marine Division, one of a relatively small number of Marines in an otherwise all-Army invasion.

McKiernan chuckles at the circumstances.

“At the time, Marines didn’t talk to the Army,” he recalled.

“And vice versa.

“I was a switchboard leader with six other [first-class privates] under me.

“We were all 18 years old, so before we left Hawaii, the communications officer said, ‘Duncan is boss, so don’t give him any lip.’”

Signing up

McKiernan, a Port Angeles native, dropped out of high school to enlist at 17.

He spent the next three years making his way around the Pacific theater of the war.

“We did some training in the Hawaiian Islands before shipping out,” he said.

“We went first to Truk Island, but the outfit I was attached to didn’t know the Allies had just dropped more bombs on Truk Island in one day than in any other operation of the war.

“They said, ‘If the bombs didn’t kill the Japanese soldiers, the sharks ate ’em up.’

“They didn’t let us in because the island had already been secured.”

From there, McKiernan and his mates went to Yap Island, where “the same thing happened.

“So then we went to Leyte and were attached to Doug MacArthur’s 6th Army.

“Everybody hated him,” McKiernan said with a laugh.

The famous picture of MacArthur striding ashore at Leyte was actually staged for the photographers, McKiernan said. “He was a sharpy.”

After his ship arrived offshore at Leyte, McKiernan and a number of his fellow Marines were loaded onto a small landing craft and pointed toward shore.

“The coxswain of the boat got mixed up and got the wrong beach. They told us to back up and go up several miles.”

McKiernan laughed again. “This was wartime. I don’t know how we won the war.

“But it came out OK,” he quickly added.

McKiernan was in charge of a portable switchboard, a hand-crank-powered radio telephone.

He was attached to the headquarters battalion, so “we were always close to where the action was generated.”

Some six weeks after arriving at Leyte, McKiernan got more action than he wanted.

“We were attacked from the rear by Japanese paratroopers,” he said.

“Because we were undermanned, we ended up in almost hand-to-hand combat.”

Grenade wound

McKiernan said he and a 19-year-old “were flat on our bellies trying to dig deeper in our muddy foxholes when we shared a Japanese hand grenade that exploded right between us.”

McKiernan later retold the story in a column in the Peninsula Daily News, saying, “Strangely, I saw a split-second vision of my mother.

“I thought I was dead.”

McKiernan said he luckily wasn’t hurt badly.

“I got a projectile in my thigh. But my buddy, I think he lost his foot.”

Two Marines came and pulled McKiernan “out of the mud and muck.”

He was soon transferred to the Army, which was responsible for his treatment.

That led to stops at five different medical facilities on the island.

Fifty-three days after landing on Leyte, McKiernan shipped out to Guam, which had previously been liberated.

In his PDN column, McKiernan recalled the event: “We arrived on Guam on Christmas Eve. Safe and sound. How joyously beautiful!”

Word from home

“I hobbled up to mail-call on crutches and got a small package from my mother and father, who lived here in Port Angeles, and a larger package from my sister,” he said.

The package from his sister, Constance, included a note saying she had packed a pint of Four Roses whiskey along with a bundle of her home-made Tollhouse cookies.

“But some sneaky Navy or Marine postal inspector along the way had detected the bottle of whiskey and pilfered it for his own use,” McKiernan said.

And the cookies? “They were full of a million tiny brown ants.”

Nevertheless, he said, it was a great Christmas.

McKiernan remained on Guam until the war ended.

“We finally got a naval transport ship to San Diego, where we were discharged,” he said.

Starting over

McKiernan made his way back to Washington, where he enrolled in high school in Seattle to earn his diploma.

He married — the first of three marriages — and moved to the Olympic Peninsula, including 14 years in Aberdeen, where he hand-built a 42-foot gaff-rigged schooner, the Windeloo.

McKiernan moved back to Port Angeles in 1975 and became the founding director of the Port Angeles Fine Arts Center.

He’s still active in the arts: This June, he received the green light to donate one of his favorite bronze sculptures to the University of Victoria.

He created the sculpture, “Homage to Elza,” in honor of Elza Mayhew, his late friend and noted Canadian contemporary.

He’s currently negotiating with Olympic National Park officials to donate a life-size bronze of a cougar, now installed at his home.

If the negotiations are successfully completed, it’s anticipated the cougar will reside at the park’s headquarters on East Park Avenue.

________

Reporter Mark St.J. Couhig can be reached at 360-452-2345, ext. 5074, or at mcouhig@peninsuladailynews.com.