By Rachel La Corte

The Associated Press

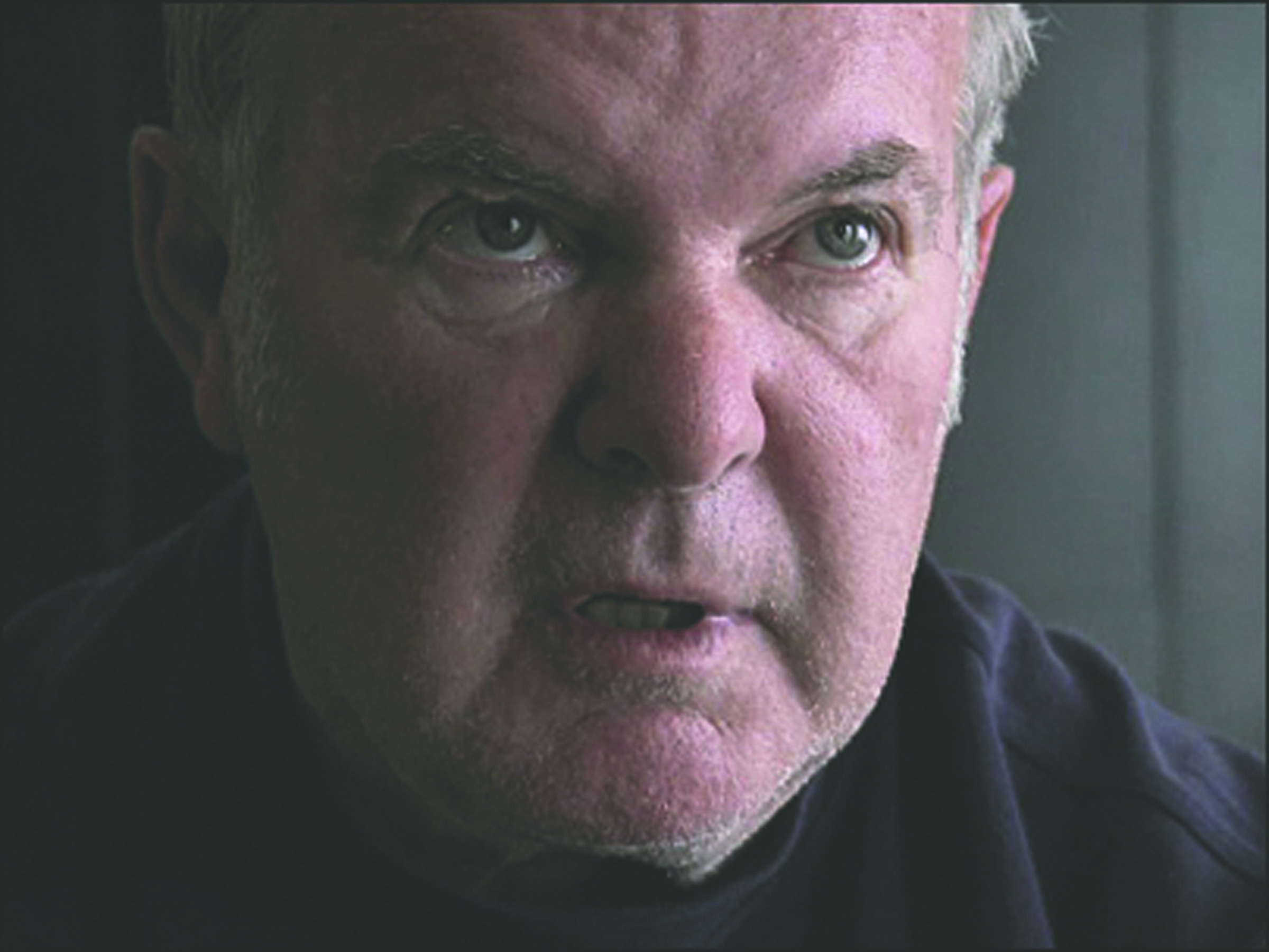

OLYMPIA — Booth Gardner was a two-term governor whose biggest political effort came long after he left the Washington state Capitol.

Gardner, who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease two years after he ended his final term as the state’s 19th governor, spearheaded a campaign that made Washington the second state in the country to legalize assisted suicide for the terminally ill.

While Gardner knew he wouldn’t qualify to use the law — Parkinson’s disease itself, while incurable, is not fatal — he said at the time that his worsening condition made him an advocate for those who want control over how they die.

He died at age 76 on Friday at his Tacoma home of complications related to the disease, family spokesman Ron Dotzauer said Saturday. He is survived by his son, Doug, his daughter, Gail Gant, and eight grandchildren.

“We’re very sad to lose my father, who had been struggling with a difficult disease for many years, but we are relieved to know that he’s at rest now and his fight is done,” Gant said in a written statement.

The millionaire heir to the Weyerhaeuser timber fortune led the state from 1985 to 1993 following terms as Pierce County executive, state senator and business school dean.

Since then, he had worked as a U.S. trade ambassador in Geneva, in youth sports and for a variety of philanthropic works. But he may be best known for what he called his final campaign: his successful “Death with Dignity” campaign in 2008 that ultimately led to the passage of the law that mirrored one that had been in place in Oregon since 1997.

“It’s amazing to me how much this can help people get peace of mind,” Gardner told The Associated Press at the time. “There’s more people who would like to have control over their final days than those who don’t.”

The law allows terminally ill adults with six months or less left to live to request a lethal dose of medication from their doctors.

The Washington law took effect in March 2009, and since then more than 250 people have used it to obtain lethal doses of medication.

A documentary about that campaign, “The Last Campaign of Booth Gardner,” was nominated for an Academy Award in 2010. A biography published by the Washington state Heritage Center’s Legacy Project, titled “Booth Who?” — after a campaign slogan on political buttons created during his first run for governor — was published that same year.

William Booth Gardner was born Aug. 21, 1936, in Tacoma to his socialite mother, Evelyn Booth and Bryson “Brick” Gardner. According to his biography, he was first named Frederick, but a few days after his birth, his parents changed his birth certificate, crossing out Frederick and replacing it with William.

While even Gardner reportedly didn’t know what led to that early confusion over his name, the change to William was believed to be a nod to his paternal grandfather, who had founded a successful plumbing and heating business in Tacoma. Even so, Gardner always went by “Booth.”

His parents divorced when he was 4 and his mother remarried Norton Clapp, one of the state’s wealthiest citizens who was a former president of Weyerhaeuser and was one of a group of industrialists who helped build the Space Needle for the 1962 World’s Fair.

Gardner had his share of tragedy: his mother and 13-year-old sister were killed in a plane crash in 1951 and his father, who had struggled with alcohol, fell to his death from a ninth-floor Honolulu hotel room balcony in 1966.

Clapp remained a presence in Gardner’s life, and though he was a Republican, he made significant donations to both of Gardner’s gubernatorial runs.

In November 1984, Gardner beat Republican Gov. John Spellman with 53 percent of the vote, winning 23 of the state’s 39 counties.

“Booth’s imprint on our state will long be seen in our classrooms and the many open spaces he fought to protect.

Up until the very end of his life Booth remained a fighter for the issues he cared most about — those of us who knew him couldn’t have imagined it any other way,” Democratic U.S. Sen. Patty Murray said in a written statement.

During his two terms, Gardner pushed for standards-based education reform, issued an executive order banning discrimination against gay and lesbian state workers, banned smoking in state workplaces, and appointed the state’s first minority to the state Supreme Court.

The state’s Basic Health Care program for the poor was launched in 1987 and was the first of its kind in the country.

Toward the end of his first term, he appointed Chris Gregoire, then an assistant attorney general, as head of the Department of Ecology. Gregoire went on to be attorney general, and then governor.

Gardner was easily re-elected in 1988, garnering 62 percent of the vote. In his second term, he and Gregoire, then attorney general, secured an agreement with the federal government that the nuclear waste at Hanford nuclear site would be cleaned up in the coming decades, and Gardner banned any further shipments of radioactive waste to Hanford from other states. The state Department of Health was also created under his watch.

“He will be remembered as a leader whose natural style of civility, respectfulness and collaboration served our state very well. We could certainly use more Booth Gardners today,” said U.S. Rep. Denny Heck, who served as Gardner’s chief of staff during his second term.

Gregoire, who stepped down as governor in January after not seeking a third term, called Gardner’s death “a huge loss to the state.”

“He was a guy where you could disagree with him on an issue, but you could never be disagreeable with him, because he would never be disagreeable with you” Gregoire told The Associated Press. “He was a unique talent.”

In 1991, Gardner announced he wouldn’t seek a third term, saying he was “out of gas.” He went on to become the U.S. ambassador to the General Agreement on Tariffs & Trade in Geneva.

While abroad, in 1995, he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. Gardner didn’t make his battle with the disease public until 2000, when he discussed it in an interview on TVW, the state’s public affairs network. That same year, he launched a clinic in Kirkland, the Booth Gardner Parkinson’s Care Center.

He announced his plan for a ballot measure to allow assisted suicide in 2006 as he continued to battle Parkinson’s. Twice in 2007, he traveled to the University of California at San Francisco for innovative deep-brain surgery that included implanting a type of pacemaker that helps restore control of his body.

Washington state had already rejected a similar assisted suicide initiative in 1991, but after a contentious campaign, where Gardner contributed $470,000 of his own money of the $4.9 million raised in support of the measure, nearly 58 percent of voters approved the new law in 2008.

In his biography, when asked how he wanted to be remembered, he responded, “I tried to help people.”

“I got out of the office and talked with real people, and I think I made a difference.”