The Associated Press

VICTORIA — Victoria’s long-delayed sewage treatment plans have become an international irritant, with Washington state demanding the British Columbia government step in to stop the flow of raw waste into the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

Gov. Jay Inslee sent a letter to B.C. Premier Christy Clark demanding that she order local Victoria-area governments to act after more than 20 years of debates and promises about treating the region’s sewage.

“It is now more than 20 years since your province agreed to implement wastewater treatment in greater Victoria, and yet today Victoria still lacks any treatment beyond screening,” Inslee wrote in Tuesday’s letter to Clark.

“Delaying this work to 2020 is not acceptable.”

Last month, Clark’s government refused to force the Victoria-area municipality of Esquimalt to accept the regional district’s plans to locate a proposed $780 million treatment facility on the shores of the community.

The Victoria region’s politicians have been scrambling ever since to develop a Plan B for sewage treatment.

Washington state supported B.C.’s bid to host the 2010 Winter Olympics partly because the province said the Victoria area would commit to sewage treatment, Inslee wrote.

The letter also recalled a 1993 tourism boycott of Victoria over the issue.

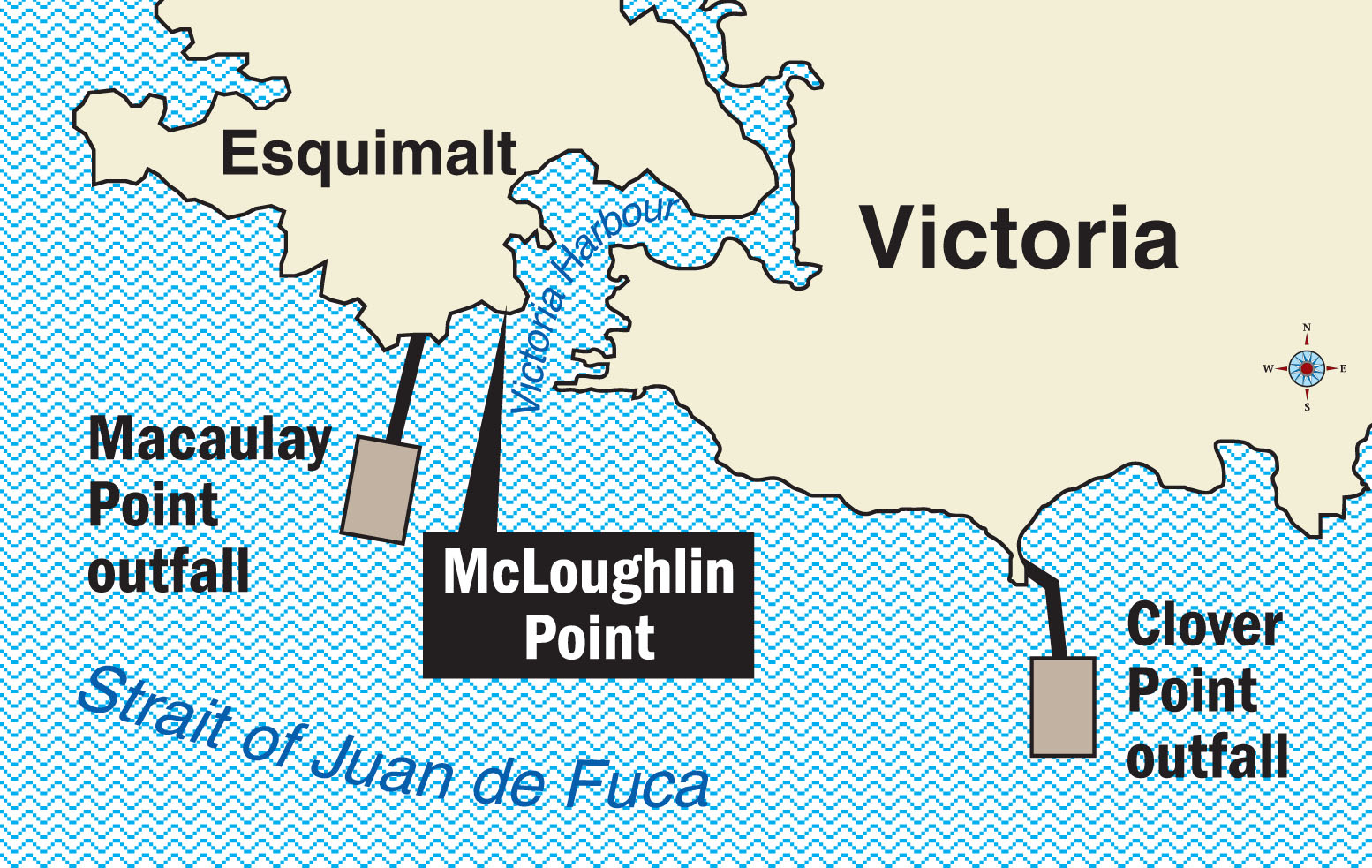

Victoria is one of the few remaining Canadian cities that does little to treat its sewage, essentially pumping 34 million gallons of raw effluent daily into the Strait directly across from the North Olympic Peninsula.

Environmentalists and communities in the United States complain of pollution, while some in Victoria say the ocean acts as a natural toilet that flushes and disperses waste with minimal environmental impact.

Inslee said the sewage issue poses health and economic issues for the area and threatens intergovernmental relations.

“Left unresolved, Victoria’s lack of wastewater treatment has the potential to color other regional and national issues at a time when our two countries are working to re-establish steady economic growth through various cross-border initiatives,” Inslee wrote.

Clark’s office directed calls about the issue to B.C.’s environment minister, Mary Polak.

“We share these concerns, which is why we have directed the [Victoria-area] Capital Regional District to deliver on its requirement for sewage treatment,” Polak said in a statement.

“We fully expect the Capital Regional District to meet both their federal and provincial requirements. We have made it clear that sewage treatment will happen; this is not up for debate.”

Polak warned that Victoria-area taxpayers could be on the hook for up to $500 million if the cities and districts within the regional district can’t decide where to locate a sewage treatment plant.

The provincial and federal governments have committed to fund two-thirds of the treatment plan project, but that money is tied to completion timelines between 2018 and 2020.

If that timeline isn’t met, local governments could end up paying, Polak said.