OLYMPIC NATIONAL PARK — One behemoth has been felled, with one left to go.

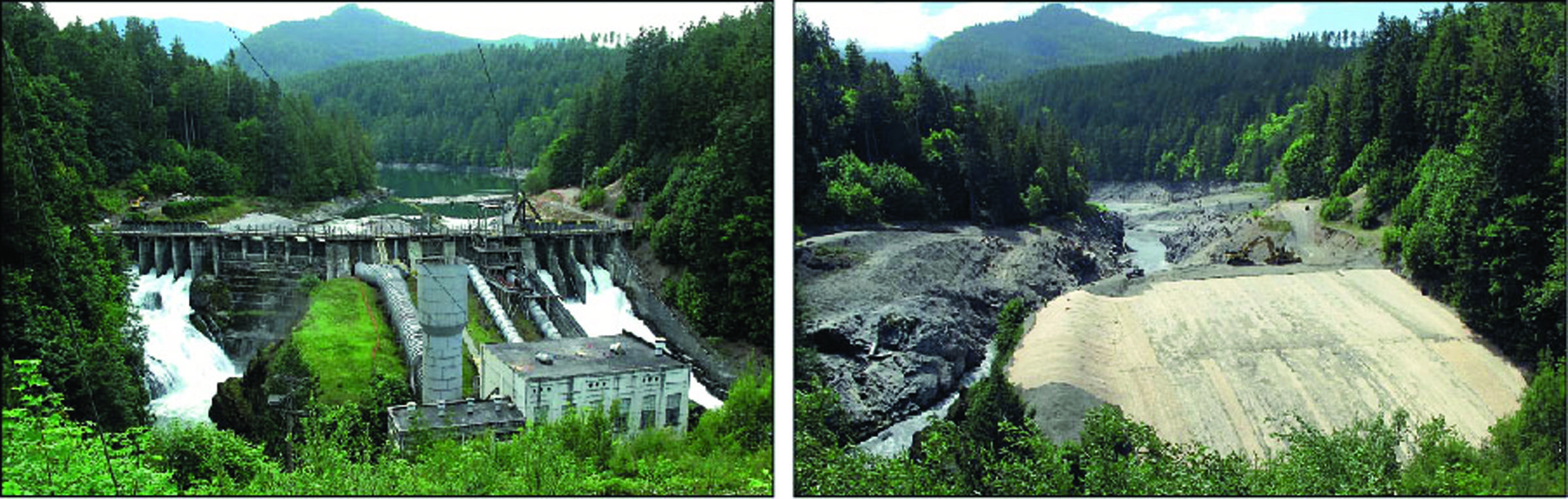

Although the monolithic Elwha River Dam, which towered 108 feet over the Lower Elwha River Valley for nearly 100 years, has been demolished, work still remains on the once-210-foot-tall Glines Canyon Dam.

And a year after removal of the Elwha and Glines Canyon dams commenced, restoration of the Elwha River is ahead of schedule — perhaps by as much as 18 months — and exceeding expectations on several fronts.

Barnard Construction Co., expects to have Glines Canyon Dam completely removed by the spring, said Barb Maynes, Olympic National Park spokeswoman.

The contract with the Bozeman, Mont.-based construction company gives them until September 2014 to complete the job.

“They’re way ahead of that [schedule],” Maynes said.

[Real-time images plus a review of the dam removals at http://tinyurl.com/pdndams ]

■ Dam removal: It took less than six months — beginning Sept. 17 and ending in March — for Barnard crews to knock out the 108-foot-tall Elwha Dam, built in 1913 5 miles from the river mouth.

That dam and Glines Canyon Dam, built in 1927 9 miles upstream, were constructed without fish ladders, blocking 70 miles of pristine habitat for migrating salmon.

Barnard Construction received the $26.9 million dam-removal contract, part of the National Park Service’s $325 million river restoration project to restore legendary salmon runs.

Crews last September began notching the top of the 210-foot Glines Canyon Dam using a hydraulic jackhammer mounted onto an excavator on a barge and, later, dynamite.

The top 120 feet of Glines Canyon Dam already is gone.

The rest will be removed through a series of controlled blasts, each requiring 30 to 60 holes drilled into the top of the dam, which began again Saturday after a six-week period called a fish window to protect migrating fish.

Barnard project manager Brian Krohmer said the most challenging part remaining in the project is likely to be the so-called apron of Glines Canyon Dam: the 13-foot-high, 36-foot-long and 60-foot-wide base.

The concrete apron still sits under the waters of Lake Mills, which means it is difficult to estimate the quantity of logs, sediment and other debris that have built up around it.

“So nobody really knows exactly what that’s going to look like,” Krohmer said.

Dealing with expected higher water flows as fall approaches and an unknown amount of built-up debris will make the next seven months or so demanding, he said.

“Trying to do that in a 60-foot-wide canyon with the river flowing in is going to be challenging,” Krohmer said.

Blasting is a slow process. The dam can be lowered by no more 1.5 feet per day, Krohmer said, but he added that crews are prepared to work seven days a week to get as much done as possible before the next fish window starts Nov. 1.

At Elwha Dam, crews diverted the river nine times between the spillway and its historic channel using coffer dams to gain access to the gravity dam.

The last remnants of the gravity dam were removed in early March.

Lake Aldwell, the reservoir formed by Elwha Dam, is gone.

At full capacity, it held 3.8 billion gallons of water, Krohmer said.

Lake Mills, the reservoir behind Glines Canyon Dam, has been reduced to a big, muddy puddle, some 9.3 billion gallons of water having been drained from it.

Barnard has used roughly 3 tons of explosives so far in removing Glines Canyon Dam, Krohmer said, and crews have blown and chipped away 54,000 tons of concrete from the Elwha and Glines dams combined.

■ Fish: In January, biologists reported that the 600 coho salmon released into Little River and Indian Creek — tributaries between the two dams — resulted in 100 salmon redds, or nests.

This summer, biologists spotted adult and juvenile chinook salmon at Altair Campground several miles upstream from the Elwha Dam site.

Meanwhile, the state Department of Fish and Wildlife counted bull trout, steelhead, chinook, pink and sockeye salmon in the fish weir below the Elwha Dam site.

■ Sediment: Scientists estimate there are 24 million cubic yards of sediment behind the dam sites, most of which is still being constricted by Glines Canyon Dam.

The goal is to let the river erode as much sediment as possible through incremental draw-downs of the reservoirs for vertical and lateral erosion.

The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that between 9 million and 10.5 million cubic yards of silt, sand, clay, cobbles and gravel will be carried downstream.

That sediment will nourish the lower reaches of the river and replenish the beaches near the river mouth, including Ediz Hook.

The rest will remain in the former reservoir beds and be covered in vegetation.

■ Vegetation: Volunteers are helping the natural revegetation of the reservoir beds by removing invasive species and planting native ones.

Joshua Chenoweth, botanical restorationist with Olympic National Park, told an audience at a science forum last month that it is too early to tell how the plants are doing because the silts take a long time to dry out.

All told, the revegetation effort will include the planting of 400,000 native plants covering 80 native species.

■ Culture: Members of the Lower Elwha Klallam tribe stood at their sacred creation site for the first time in nearly a century in July.

The site was flooded when Elwha Dam was built in 1913.

Oral tradition and recorded reports dating as far back as 1919 described the rock as the place where the Creator bathed and blessed the Klallam people and other tribes.

It also was a place for vision quests, where tribal members would discover their calling in life, Klallam language instructor Jamie Valadez has said.

Receding lake water also revealed one of the oldest known archaeological sites on the Olympic Peninsula, the park said.

Radiocarbon analysis of the area — at a separate place from the creation site — showed that people had lived there as far back as 8,000 years ago, park officials said.

Both sites are off limits to the public, and no specific location information has been released.

■ Other findings: A human leg bone was found in the Lake Aldwell bed May 15.

The discovery prompted the Clallam County Sheriff’s Office to reopen a cold case involving a missing woman, 41-year-old Karen C. Tucker, who had been reported missing Jan. 5, 1991.

________

Reporter Rob Ollikainen can be reached at 360-452-2345, ext. 5072, or at rollikainen@peninsuladailynews.com.

Reporter Jeremy Schwartz can be reached at 360-452-2345, ext. 5074, or at jschwartz@peninsuladailynews.com.